35 years ago this week, the crew operating a routine transcontinental US passenger service faced a dramatic, unprecedented situation. A violent and destructive engine failure on the aircraft, one of United Airlines’ McDonnell Douglas DC-10s, caused the loss of all standard flight controls through the fracture of all three hydraulic syst ems on the aircraft.

Unable to turn, climb, or descend the aircraft using conventional flight control inputs and effectively left to fly an unflyable airplane, the crew were forced to rely on engine power alone to find and reach a suitable airfield and attempt a landing. With 296 passengers and crew onboard that day, the stakes could not have been higher.

And yet, with professional calmness and supreme skill, working as a team in the most desperate of situations, the crew pulled off the impossible and landed the aircraft. While fatalities resulted, the majority of those onboard survived. This is the remarkable story of United Airlines Flight 232 – the miracle of Sioux City.

Background to Flight 232

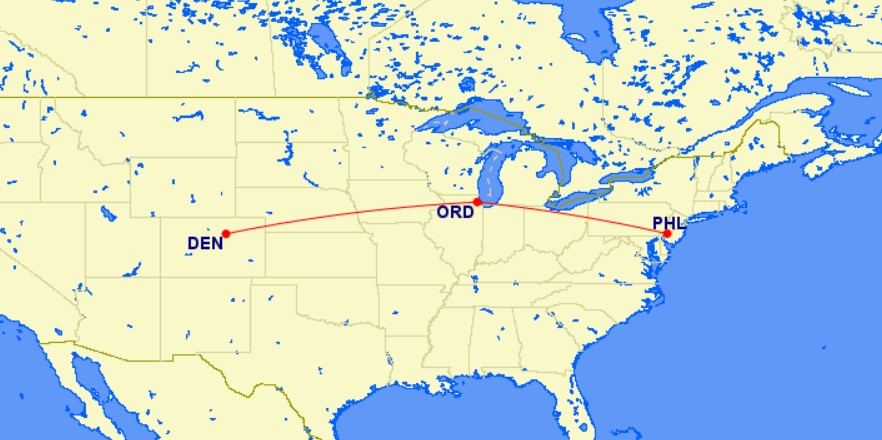

On July 19, 1989, a United Airlines DC-10 was tasked with operating flight number UA232 on a routine scheduled passenger service from Denver-Stapleton International Airport (DEN) to Chicago-O’Hare Airport (ORD), continuing on to Philadelphia Airport (PHL).

The aircraft assigned to operate Flight 232 was one of the company’s 55 McDonnell Douglas DC-10s, registered as N1819U. The plane had been delivered new to United in 1971 and had since accumulated a total of 43,401 hours and 16,997 cycles (take-offs and landings) during its 18-year career.

The aircraft was powered by three General Electric CF6 turbofan engines, with one mounted under each wing and a third located above the rear fuselage in the base of the tail.

N1819U carried United’s then-current livery, which featured horizontal layered orange, red, and blue cheatlines along the fuselage, with the company’s ‘tulip U’ logo displayed on the tail in the same colors.

Crew details

The flight crew of Flight 232 consisted of a captain, a first officer, and a flight engineer, accompanied by eight flight attendants.

The captain was 57-year-old Albert ‘Al’ Haynes. Haynes had been employed by United since February 1956 and had accrued 29,967 hours of flight time, 7,190 hours of which had been on the DC-10.

The first officer was Bill Records, 48. He had been flying for United since 1969. The flight engineer was Dudley Dvorak, 51, who had been hired by United in 1986. The crew, who had flown together six times in the previous 90 days, had enjoyed a 22-hour layover in Denver before the departure of Flight 232.

Also onboard that day was an off-duty United training captain, Dennis ‘Denny’ Fitch, 46, who had flown for United since 1968. Fitch had over 23,000 flying hours in his logbook, of which around 3,000 were on the DC-10.

Departure of Flight 232

All closed up and ready for departure on a fine summer’s day, Flight 232 departed Denver at 14:09 local time for the first leg of its journey to Chicago.

285 passengers and 11 crew members were on board the flight that day. The take-off and the en-route climb to the planned cruising altitude of 37,000ft (11,280m) was uneventful, with the first officer as the flying pilot.

Catastrophic failure of engine #2

At 15:16, around an hour and seven minutes after departure from Denver, the flight crew noticed a loud bang from the aircraft, likened to an explosion. They subsequently experienced severe airframe vibration and set out to discover the cause. On scanning the engine instruments, it quickly became apparent that the number two tail-mounted engine had failed.

Captain Haynes ran through the emergency engine shutdown checklist with the First Officer Records while the flight engineer continued to scan his instrument panel. On checking the hydraulic fluid pressure and quantity gauges, he noticed that they all read zero.

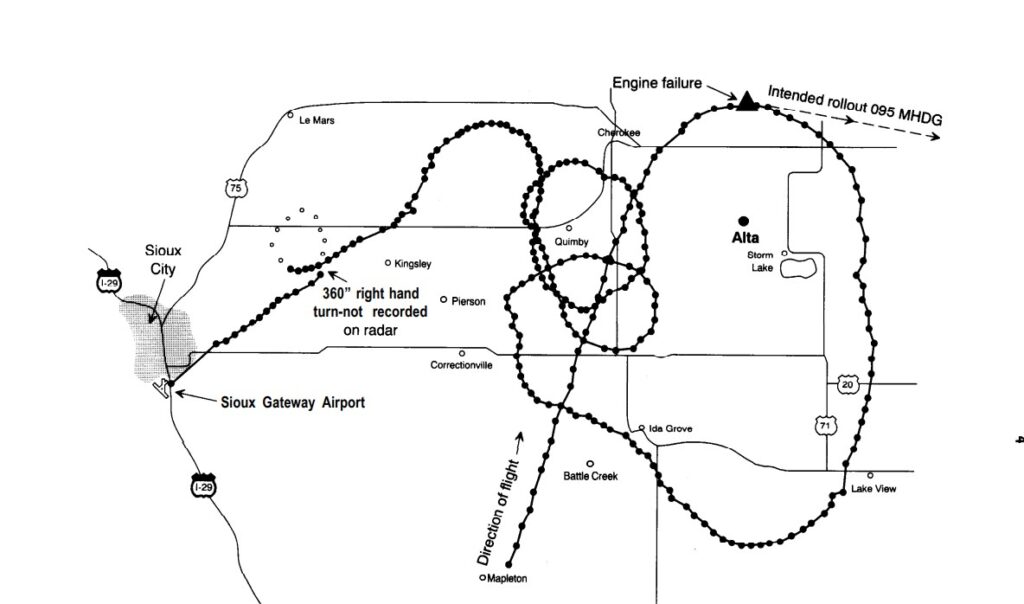

The primary flight controls on the DC-10 (ailerons, rudder, elevators, spoilers) were all operated by hydraulic pressure and the first officer was quick to realize that his controls were unresponsive to his inputs. The plane entered a descending right-hand turn.

Haynes took the controls and, noting the same control issues, reduced thrust on the number one engine, which resulted in the aircraft rolling out in a wings-level attitude, giving the crew critical time to evaluate the dire situation Flight 232 was facing.

Decision to divert

Four minutes later, at 15:20, the crew called air traffic controllers in Minneapolis and requested a diversion to their nearest available airport. Following further discussion and analysis of the flight’s route, Flight 232 was given instructions to divert to Sioux City Gateway Airport (SUX) in Iowa.

It was at this point that Denny Fitch, the off-duty training captain seated in the first-class cabin, offered his assistance and entered the flight deck of N1819U at 15:29. His decision to do so would prove to be a turning point in the handling of the incident.

Flying the unflyable airplane

Having quickly assessed the state of the aircraft’s wings from the passenger cabin, Fitch reported that there was no movement from any of the flight control surfaces on the wings. Haynes asked that Fitch assume control of the engine throttles, by kneeling between the two forward-facing pilot seats. This was to free up Haynes and Records to hold their control columns while they attempted to regain some control of the airplane.

Fitch operated the engine throttle levers and used differential engine power settings to control the aircraft’s pitch and roll. He reported that the plane displayed an ongoing tenancy to bank to the right and manipulated the two remaining engine throttles (numbers one and three) with both hands to control the aircraft’s attitude.

At 15:42, the flight engineer was dispatched from the flight deck to perform an inspection at the back of the cabin. Upon his return, he reported that both right-hand and left-hand rear stabilizers had sustained damage.

Following this, the crew began dumping fuel to lower the landing weight of the aircraft and, as the landing gear lowering procedure was reliant on hydraulic pressure, the gear had to be lowered using the manual alternative extension procedure.

Fitch reduced the power settings as the aircraft limped its way toward the designated diversion airfield at Sioux City. He used the first officer’s airspeed indicator and visual cues out of the cockpit windows to determine the flight path of the plane and the need for any power changes.

The approach to Sioux City

With the aircraft at a range of about nine miles from touchdown at Sioux City, the crew made visual contact with the airport. Having initially been given the option to land on runway 31, which was 8,999ft (2,743m) in length, the crew advised that, as they were unable to turn the aircraft in the distance remaining towards that runway orientation, they were instead committed to land on runway 22, which was just 6,600ft (2,012m) long.

With the landing gear down but without the use of the wing leading-edge slats and trailing-edge flaps, there was little the crew could do to control the stricken aircraft’s approach speed, other than through variable engine power settings.

During the final approach, Haynes noted a high sink rate alarm from the aircraft’s ground proximity warning syst em (GPWS). The subsequent investigation discovered that in the last 20 seconds prior to touchdown, the airspeed averaged 215 knots (247 mph/395 kph) while the sink rate was 1,620ft (493m) per minute – both excessive for the DC-10.

Fitch continued to make small manipulations of the engine controls as the aircraft crossed the runway threshold, still maintaining a straight and level attitude but at a landing speed much higher than normal.

Fitch later told investigators that he thought the airplane was “fairly well aligned with the runway during the latter stages of the approach and that they would reach the runway”.

Right before touchdown, at around 100ft above the runway, the right wing suddenly and violently dropped, and the aircraft’s nose pitched down. Fitch added power just before touchdown to soften the landing as the aircraft’s right main gear made contact with the runway surface.

Touchdown

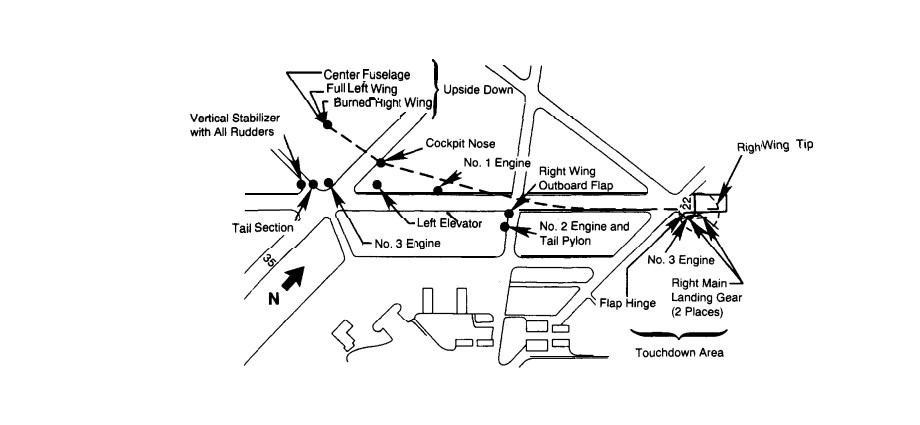

At 16:00 the airplane touched down on the runway threshold to the left of the centerline. First ground contact was made by the righthand wing tip, followed by the right main landing gear.

Due to the late wing drop, the airplane slewed to the right of the runway and rolled over to an inverted position. Witnesses, plus amateur camera footage taken at the time of the landing, saw the plane land at high speed before cartwheeling over to the right and igniting as a post-crash fire ripped through the wreckage. The aircraft eventually came to rest to the right of runway 22 after the intersection with runway 17/35.

Note: The video below contains footage that some readers may find distressing to watch.

With the airport’s fire and rescue services on standby as the plane landed, firefighting operations began immediately.

The crash landing resulted in the loss of 111 passengers who were fatally injured either from the impact or from the effects of the post-crash fire. There were also 47 passengers and crew seriously injured with 125 others receiving minor injuries. 13 occupants onboard the plane were uninjured. One person later died as a result of injuries sustained during the landing.

All four flight crew members escaped with their lives, along with 62% of all those onboard Flight 232.

Damage to the aircraft

Amateur photos taken as N1819U approached Sioux City showed parts of the plane’s number two engine cowling and its fuselage tail cone were both missing. A subsequent post-crash examination of the wreckage revealed that components of the engine’s forward fan rotor had separated from the engine in flight and pierced the engine cowling, impacting the horizontal stabilizers and rear fuselage empennage.

The airplane’s right wing fell apart upon impact with the ground, while the rest of the aircraft broke up as it overturned down the runway. The fuselage center section, with much of the left wing still attached, came to rest in a cornfield to the right of runway 22, The cockpit separated early on in the impact sequence and came to rest at the edge of runway 17/35.

The largely intact tail section continued down runway 22 and came to rest on an adjacent taxiway, while the two wing-mounted engines both separated during the landing.

Investigation and findings

Following the accident, the National Transport Safety Bureau (NTSB) dispatched a team to Sioux City to begin gathering evidence and determine the series of events that had caused the crash landing of Flight 232.

Along with taking photos and conducting a full analysis of the landing sequence and subsequent breakup of the aircraft, the investigators also interviewed hundreds of witnesses, including the flight crew, passengers, and others on the ground who saw the aircraft in its final stages of flight and landing.

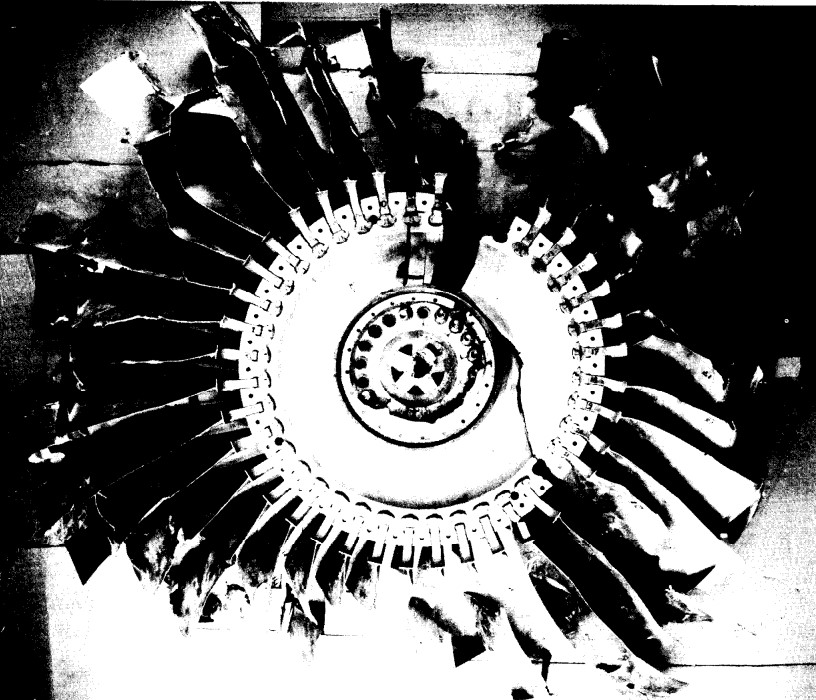

Incredibly, in mid-October 1989, around three months after the accident, two major sections of the engine number two fan disk with attached blade pieces were found in a corn field near the town of Alta in Iowa, some 66 miles (106km) from Sioux City Gateway Airport.

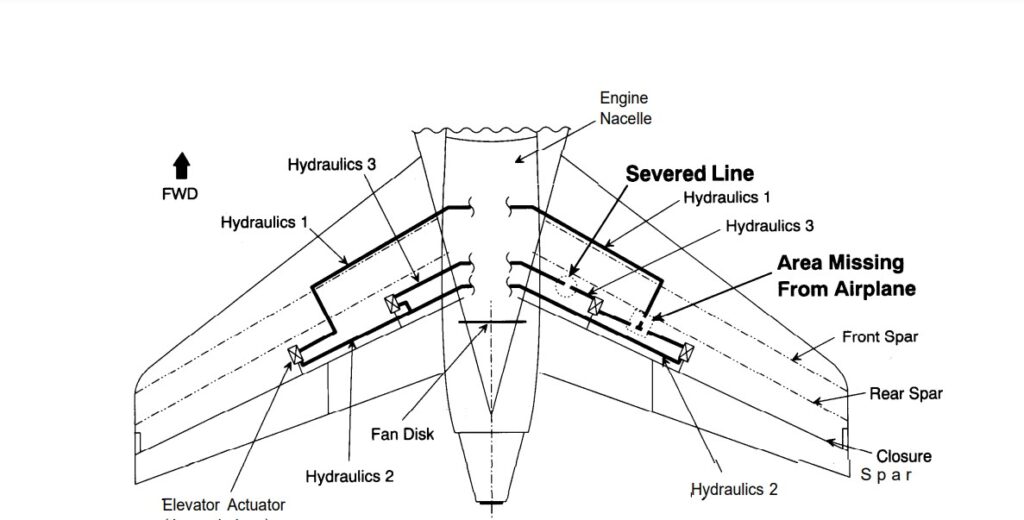

Metallurgical analysis of these parts carried out by the NTSB found that fatigue cracks in the components had fractured, causing the fan disk to separate from the drive shaft at high speed. The fractured parts spun through the engine casing and cowling and departed the aircraft, with smaller parts piercing the horizontal stabilizer on both sides and the rear fuselage.

With each of the three hydraulic syst ems congregated around this section of the aircraft, each sustained high-energy impact damage from fast-moving engine parts, causing the sudden and catastrophic loss of all hydraulic fluid from each of the syst ems. This in turn led to the crew’s loss of ability to manipulate the flight controls and fly the airplane in the conventional manner.

Fitch subsequently described the chances of losing all three hydraulic syst ems at once as “one in a billion”.

NTSB findings

On November 1, 1990, a year and three months after the accident, the NTSB published its final report on Flight 232.

The investigation found that deficiencies in United Airlines engine component maintenance and inspection procedures had meant that the fatigue cracks in the engine number two fan disk had long gone undetected and unrectified.

Over time, with the aircraft performing additional cycles throughout, these cracks expanded and eventually sheared, causing the detachment of the fan disk and leading to the uncontained engine failure. The components that sheared away exited the engine cowling and ruptured the hydraulic lines of the aircraft, leading to the loss of flight control authority.

The report concluded: “The National Transportation Safety Board determines that the probable cause of this accident was the inadequate consideration given to human factors limitations in the inspection and quality control procedures used by United Airlines’ engine overhaul facility which resulted in the failure to detect a fatigue crack originating from a previously undetected metallurgical defect located in a critical area of the stage one fan disk that was manufactured by General Electric Aircraft Engines.”

“The subsequent catastrophic disintegration of the disk resulted in the liberation of debris in a pattern of distribution and with energy levels that exceeded the level of protection provided by design features of the hydraulic syst ems that operate the DC-10’s flight controls.”

What happened to the crew of Flight 232?

Although 111 of those onboard lost their lives when Flight 232 crash-landed, 185 survived. This achievement was seen as a testament to the heroic airmanship of Captain Haynes and the crew of Flight 232, plus the efforts of Denny Fitch, the off-duty pilot who controlled the engine power levers as the aircraft struggled toward Sioux City.

While the plane had been rendered virtually unflyable through the loss of all three hydraulic syst ems, the stoic crew, while facing immense pressure in an unprecedented situation, still managed to fly the plane and get it on the ground, saving the lives of 185 people.

Captain Haynes continued his flying career with United Airlines after the incident involving Flight 232. He eventually died in August 2019 after a short illness, just six days before his 88th birthday. Haynes always maintained his public praise for the cabin crew who helped to evacuate so many passengers after the plane had landed.

Captain Denny Fitch also continued to fly with United, ultimately dying of brain cancer in May 2012. Like the rest of the crew, Fitch always rejected claims that the group were heroes, insisting they were all just doing their jobs as pilots.

In an interview some years after the events of Flight 232, Fitch also alluded to the guilt he and his pilot colleagues had faced through not being able to save everyone onboard the aircraft.

“I was 46 years old the day I walked into that cockpit,” he said. “I had the world ahead of me. I was a captain of a major US airline. I had a beautiful healthy family, a loving wife, and a great future. And at 4 o’clock, I’m trying to stay alive.”

“To find out 112 people didn’t make it, that just about destroyed me. I would have given my life for any of them.”