On this day 30 years ago, a British Aerospace 146-100 four-engine jet operated by the Royal Air Force (RAF) suffered a mishap when landing on the Scottish Island of Islay in the Inner Hebrides archipelago.

What made this accident particularly newsworthy was not the aircraft type, nor the location in which it happened, but the pilot flying the aircraft that day – none other than King Charles III (then Charles, Prince of Wales), the current monarch of the United Kingdom.

AeroTime takes a closer look at the accident itself, the repercussions arising from it, and where the aircraft involved ended up following its royal mishap in 1994.

Background to the accident

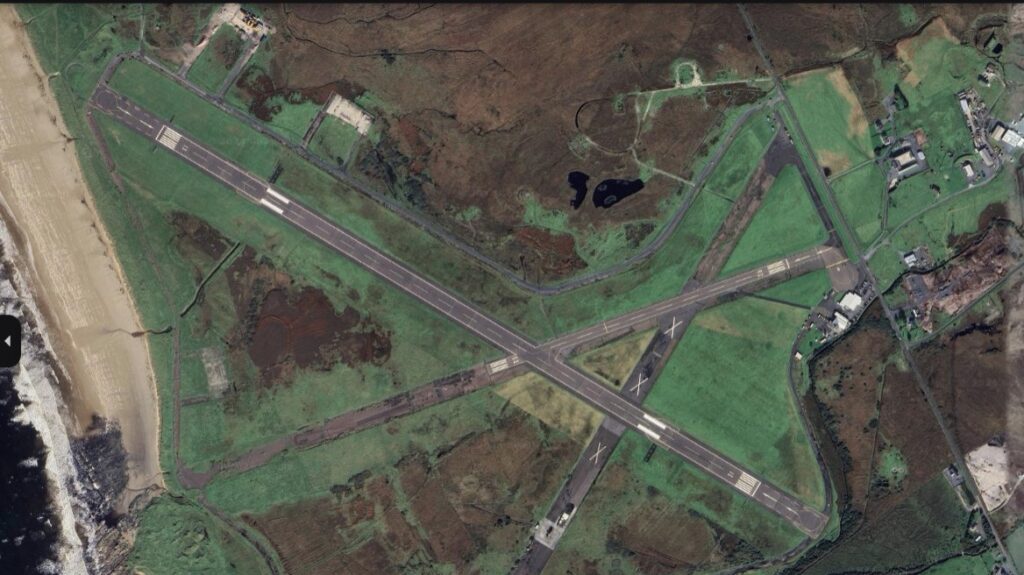

It was June 29, 1994, at around 11:50 on the Scottish island of Islay, located around 150 miles west of Glasgow in the collection of islands known as the Inner Hebrides. Islay Airport (ILY) has a primary tarmac runway 13/31 with a total length of 1,545m (5,069ft) – relatively short compared to the major Scottish airports of Aberdeen (ABZ), Glasgow (GLA), Edinburgh (EDI), and Inverness (INV), yet still capable of handling both propellor and jet aircraft.

Charles was traveling to the island for several local engagements on one of the two British Aerospace 146-100s (referred to by the RAF as a ‘146 CC2’) operated by 32 Squadron of the RAF, also known as ‘The Royal Squadron’. Tasked with flying members of the UK royal family to public and private engagements both within the UK and abroad, the small red, white, and black quadjets were a regular sight at airports across the UK and Europe at the time.

The aircraft involved in the accident, carrying RAF tail number ZE700, was tasked with transporting Charles that day from earlier engagements in Aberdeen on the mainland. As a holder of a UK Pilots’ Licence himself, Charles was known to regularly fly himself and often took the controls of the Royal Flight aircraft when traveling on them to meetings or engagements.

On the day in question, he occupied the captain’s (left-hand) seat in the flight deck of the 146 as the pilot flying (‘PF’), with the hugely experienced Squadron Leader Graham Laurie acting as the co-pilot (or pilot monitoring ‘PM’) in the right-hand seat.

The landing attempt at Islay

With the weather conditions at Islay Airport overcast, with gusty winds, but generally dry, the aircraft made its approach to the airport from the north intending to perform a full-stop landing.

The landing was to be made on runway 13, which had a published landing distance available (LDA) of 1,245 m (4,083 ft). At the time of the landing attempt, the wind was blowing at 250 degrees at 20 knots (23mph/37kph), giving a tailwind component down the runway of 12 knots (14mph/23kph).

The Board of Inquiry later described the 146’s approach to the runway be “unstable” and above the desired approach path. Additionally, the aircraft’s approach speed was well in excess of the prescribed speed given the weather conditions and runway length.

The aircraft’s speed across the threshold was reported as 32 knots (37 mph/60 kph) higher than it should have been at that critical point. The excessive speed, when combined with the high approach and the tailwind component led to the aircraft touching down well down the runway, with only around 784 meters (2,571 ft) remaining for the roll-out and deceleration.

The aircraft touched down on its nose landing gear (NLG) first, and ‘wheelbarrowed’ – where the main landing gear (MLG) is delayed from making contact with the runway surface due to the high speed of the air passing over the wing continuing to produce lift. The failure of the MLG to make firm contact with the tarmac delayed the activation of the weight-on-wheels switches and hence the deployment of the lift spoilers and the automatic selection of ground idle power from the aircraft’s four engines.

Additionally, investigators found the MLG wheel brakes were applied before the anti-skid protection system’s full activation which caused both inboard main wheels to lock and the failure of both tires. The weight-on-wheel switches eventually activated with just 509m (1,669ft) of the runway remaining.

Unable to stop in the distance remaining, hampered by the loss of braking ability on two main tires and the excessive speed brought about by the delayed activation of the spoilers, the aircraft ran off the end of the runway and into a ditch. The plane was substantially damaged as a result.

The airport fire and rescue service attended the scene while Charles was quickly whisked away in his motorcade to continue with his itinerary, leaving the other crew to deal with the fallout from the accident.

Subsequent investigation

As the accident involved a military rather than a civilian aircraft, it was an RAF Board of Inquiry that investigated the events leading up to the botched landing and the subsequent overrun.

It was reported, following the conclusion of the investigation, that the Board found the captain (Charles) to be “negligent in that he failed to intervene [with positive control inputs] when the aircraft performance and limitations were exceeded in the final stages of the flight”. The navigator (Squadron Leader Laurie) was also found negligent for “failing to advise the captain of the tailwind component and to draw his attention to the inaccurate approach parameters.”

“It was not quite a crash,” The Herald Scotland newspaper quoted Charles as saying after the accident. “We went off the end of the runway. It’s not something I recommend happening all the time, but unfortunately, it did,” he added.

“With hindsight, which is a wonderful thing, I should have got him to overshoot and try a different approach, but I told him to land, so he did exactly what he was told to do,” said Squadron Leader Laurie, speaking to The People newspaper in an interview some months later.

The damage caused to ZE700 during the landing and overrun was reported to have cost UK taxpayers well over £1 million ($1.27m at current exchange rates) to repair. The aircraft returned to flying duties with 32 Squadron following extensive repairs and was finally retired in 2022 (see below).

Aviation experts still consider the landing to technically be classified as an accident rather than an incident, with some even referring to it as a ‘crash’, given the extent of the damage suffered by the aircraft.

King Charles’ flying career

Charles first became actively involved in flying as a young student at Cambridge University in the UK. Charles received his basic flight training with the University Air Squadron (UAS) based at Cambridge Airport and made his first flight in January 1969 flying a De Havilland Chipmunk nicknamed the “Red Dragon”.

This low-wing single-engine trainer held a pilot and their instructor in a tandem configuration (one sitting behind the other).

During his time in the UAS, Charles completed 101 flights in the aircraft while under the supervision of UAS flight instructor Squadron Leader Philip Pinney. Charles, then the Prince of Wales, was in his early 20s at the time. By March 1969, Charles had successfully obtained his pilot’s license.

After completing his undergraduate degree in archaeology and history at Cambridge University in 1970, Charles joined the RAF in 1971. In fact, according to his official website, Charles flew himself to the training facility in Cranwell, Lincolnshire. After earning his coveted RAF ‘wings’, Charles went on to attend the Royal Naval College. He then trained as a helicopter pilot and joined a Royal Naval Air Squadron. His official naval military service ended in 1976.

While Charles served in both the RAF and Royal Navy, he still had outside engagements to keep up with as a British royal. Interestingly, Charles would often fly himself to such events, operating aircraft belonging to 32 Royal Squadron. He regularly flew planes as part of the Royal Squadron up through the mid-1990s.

However, the accident in Islay was to change all that. Having flown for over two decades, in 1995 Charles decided to hand in his wings, give up his pilot’s license, and call a halt to his flying days. Since that day in Islay, Charles has left the flying duties to others, preferring to be a passenger rather than the pilot on flights he now undertakes while performing both public and private duties.

Where is ZE700 now?

The aircraft involved in the Islay accident, ZE700, returned to active service with 32 Squadron several months after its recovery and repair. It continued to fly members of the UK Royal Family (including Charles), along with senior government ministers and Ministry of Defence personnel for another 27 years until finally being retired in 2022.

The two 146 CC2s flown by the RAF were replaced by modern Dassault 900LX jets which were more sustainable thanks to their smaller engines, which resulted in a reduction in fuel burn and emissions. They also offered a much longer range than the 146s could manage.

On March 16, 2022, ZE700 was ferried from its base to the former RAF airfield of St Athan Airport (DGX) near Cardiff in Wales. During its final flight, the aircraft carried out several flypasts at key airports and airfields that were key to the history of the aircraft including RAF Brize Norton, Glasgow Prestwick Airport, and Warton Aerodrome, a key British Aerospace (now BAE Systems) site.

Once safely at St Athan, the plane took up residency at the South Wales Aviation Museum (SWAM). Having been donated to the Museum by the RAF, the aircraft was stripped of its specialist electronic equipment before it was formally handed over to the museum operators.

The aircraft was named after Group Captain Lionel Rees VC, a Welsh fighter pilot from Caernarfon who was awarded the Victoria Cross in the First World War. Rees was awarded Britain’s highest award for gallantry for his actions on June 1, 1916, the first day of the Battle of the Somme, after single-handedly taking on ten enemy aircraft.

ZE700’s sistership and the only other 146 CC2 operated by the RAF (ZE701) was retired later that same year (2022) and now forms part of the British Airliner Collection of aircraft at the Imperial War Museum located at Duxford Airfield near Cambridge, England.