An essential component of modern aircraft making is the element Titanium, chemical symbol Ti.

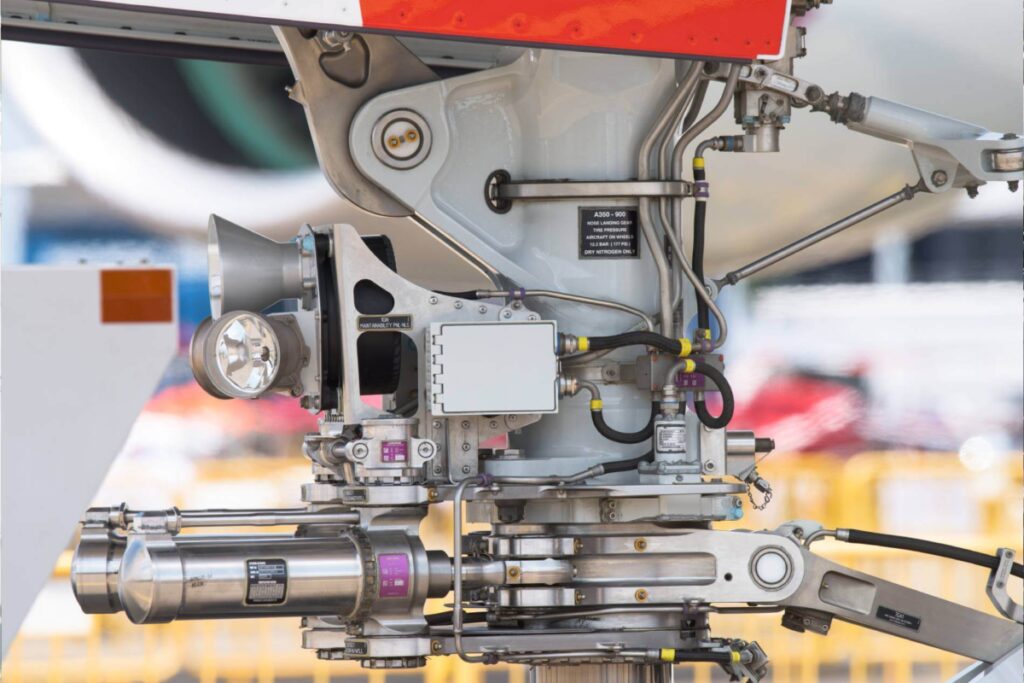

From sections of the fuselage frame and engine blades to landing gear and the numerous bolts and fasteners that hold sections of the aircraft together, the list of aircraft components containing titanium alloys is extensive.

The aerospace industry has long recognized the properties of this highly tensile metal. Titanium is resistant to heat and corrosion and boasts a high strength-to-weight ratio. It offers a strength similar to that of steel, but at a fraction of the weight. This is particularly crucial in an industry that is eager to find ways to cut down on weight in order to make planes more fuel efficient.

What’s more, titanium can be combined with composites, plastic-like lightweight materials increasingly used in aircraft manufacturing.

The degree to which titanium is used in aircraft manufacturing continues to increase. While the first version of the Boeing 747, developed in the 1960s, included less than 3% titanium, that proportion jumped to almost 9% in the first version of the Boeing 777 which flew in the mid 90s. In contemporary airliners such as the Boeing 787-9, the amount is closer to 15%.

More than half of the world’s titanium supply is consumed by aerospace manufacturing and any disruption to the supply of this essential metal could sent shockwaves across the industry.

Many industries have been affected by generalized supply chain issues in the last couple of years, but the global titanium market has had to deal with problems of its own, given that a large share of the world’s titanium supply comes from Russia.

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 led to both Airbus and Boeing announcing a reshuffling of their titanium supply chains.

Before the war, Russia had been a major titanium supplier to both Boeing and Airbus.

In fact, the role of Russia as a source of titanium was such that the American aircraft manufacturer had even set up a joint venture with VSMPO-AVISMA, which is part of Rostec, an industrial and defence conglomerate owned by the Russian government.

As recently as November 2021, barely three months before the start of the war and with tensions with Ukraine already running high, Boeing and VSMPO-AVISMA signed an agreement to prolong and expand their collaboration. It is estimated that around one third of the titanium used by Boeing came from Russia.

In the case of the Airbus, reliance on Russian titanium supplies was even more significant. There was no joint venture in place comparable to the one between Boeing and VSMPO-AVISMA, but even so, the European aircraft manufacturer is said to have been sourcing around half of its required titanium from Russia.

The war has changed that completely.

As soon as Russian tanks started to roll towards Kyiv, both Boeing and Airbus announced they were dissociating themselves from their respective Russian procurement deals.

Even by March 2022, Boeing was announcing that it had sufficient titanium stocks to keep up with its regular production rates and that it had managed to find alternative suppliers for its titanium needs.

In response to questions from AeroTime, a source at Boeing stated: “Boeing currently sources titanium predominantly in the U.S. We suspended the purchase of Russian titanium in March 2022” – thereby confirming the move away from Russian titanium.

Airbus also announced its willingness to stop buying Russian titanium, although the decoupling appears to have been taking longer to implement. As of December 2022, reports in the media suggested that Airbus was still struggling to cut its ties to Russian suppliers.

Unlike with other commodities, Russia is not in fact the primary source of titanium ores.

They are mined in places like China, Australia, Kazakhstan, Mozambique – and, rather remarkably in the circumstances, Ukraine.

Russia’s importance in the titanium supply chain is based on its position in the further stages of processing, with VSMPO-AVISMA being a major producer of titanium sponge, which is the form into which the metal is first smelted, turning it into a porous material.

After that, titanium is further processed to make ingots, panes and other semi-processed forms. These are then further transformed, via the use of specialized machine tools, into all manner of parts and components.

Outside of China, the other major players in the titanium market are Japanese companies such as Osaka Titanium and Toho Titanium.

Not surprisingly, global titanium prices shot up by around 90% in the months following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The market seems to have calmed down somewhat since then, with prices stalling and even starting to revert back to pre-war levels. That’s according to Prashant Metha, managing partner at Titanium Horizon, a titanium trading firm based in Ahmedabad, India, which works mainly with the aerospace and medical industries.

The solution is therefore not so much a matter of getting access to sources of raw material, but of reshuffling the production capacity at different stages of the titanium transformation process.

A 2022 report by Efeso Management Consultants, a consultancy firm specialized in optimization of industrial processes, concluded that US and Japanese firm – though not so much their European counterparts, since these industrial capabilities are mostly absent in Europe – should be capable to build additional titanium processing capacity. However, in execution this would take several months and significant capital investment running into dozens of millions of dollars.

Stock prices of both Osaka Titanium and Toho Titanium more than tripled in the months following the outbreak of the war in Ukraine.

While industrial capacity in the titanium industry is reorganized to reflect this new reality, aerospace firms may need to rely a lot more on existing stocks and the scrap market – that is, reusing metal chips cut away during the titanium metalworking process.

“Since titanium has become a lot scarcer and more expensive, the value of the chips that come out of the cutting process has increased, because these can be recovered, remelted and reworked,” explains Dean Richmond, Global director of Aerospace at Master Fluid Solutions, a company that provides fluids used as a lubricant and coolant during the titanium cutting process.

In an example of how a geopolitical shock can reverberate through the most unexpected segments of an industry, Richmond explained to AeroTime that Master Fluid Solutions had noticed increasing demand for its specialty fluids. Those contain particles called microsols that speed up the drying process for titanium scrap chips, making it possible for operators to re-introduce them into the industrial reprocessing chain more quickly.

Regardless of what happens in the frontlines in Ukraine, it’s therefore likely that the industry will undergo a major, long-lasting reorganization that should see American and Japanese companies take a more prominent role. Meanwhile Russia, mimicking what has happened in other industries, may lean towards China.

Prashant Metha, of Horizon Titanium, is bullish on the prospects of the titanium market, particularly in the Asia-Pacific region. “Many countries, India, China, Korea…are building up their aerospace industries as well as all the related auxiliary industry to make parts and components and they are going to need larger quantities of titanium in years to come,” he affirmed.

A big question mark is what kind of role Europe might play in the future of the industry. The EU is a major player in the global aerospace industry, with major companies such as Airbus, Rolls-Royce and Safran. Surprisingly, though, it lacks any significant presence in the titanium processing market. Will European industrialists and policymakers see the titanium supply chain as an area in which they might further develop the continent’s strategic autonomy?