Alaska Airlines Flight 261 was one of the worst aviation disasters in modern US history. What should have been a routine flight turned into a tragedy after a part of the tail assembly failed.

Twenty-five years on from this terrible accident, we look back at what led up to the crash, what was learned from it, and why the pilots Ted Thompson and Bill Tansky are now hailed as heroes for their actions during the incident.

Alaska Airlines Flight 261: A routine flight

Flight AS261 was a routine service traveling from Licenciado Gustavo Díaz Ordaz International Airport in Puerto Vallarta, Jalisco, Mexico, to Seattle–Tacoma International Airport in Washington, with an intermediate stop at San Francisco International Airport in California.

On January 31, 2000, this flight was to be operated by a McDonnell Douglas MD-83 registered N963AS. It was eight years old and had logged just over 26,000 flight hours and 14,000 cycles since delivery.

Flying the aircraft were two highly experienced former military pilots. Captain Ted Thompson, aged 53, had flown more than 4,000 hours in MD-80s, while First Officer Bill Tansky, aged 57, had accumulated over 8,000 hours on the MD-80 family. Previously, Thompson had flown for the Air Force, Tansky for the US Navy.

In all, there were 88 occupants on board: 83 passengers and five crew. The incoming crew had enjoyed a completely normal journey, with no problems or issues reported. It was a beautiful day for flying, with good visibility and light winds. The flight took off on time at 13:37 PT, with First Officer Tansky at the controls.

First indications something wasn’t right: A problem with the climb

Tansky took the aircraft manually to around 6,200 feet, where he engaged the autopilot. The aircraft continued to climb towards the target altitude of 31,000 feet, but indications were starting to suggest something wasn’t right.

The aircraft was slowing down, and so too was the climb. The aircraft levelled off at 26,000 feet, so Tansky disconnected the autopilot and took manual control again. There are no voice transcripts from this part of the flight, as only the last 30 minutes were recorded, but undoubtedly First Officer Tansky would’ve noticed a large force of as much as 50 pounds was required to keep the aircraft climbing.

The trim on the horizontal stabilizer – the rear wing of the aircraft – was not working. As such, Tansky had to rely on elevators alone to climb to 31,000 feet. As they levelled off, the force required to maintain altitude lessened, but was still at around 30 pounds of pressure. Something was badly wrong.

The pilots went through their quick reference handbook, performing all the necessary checklists to try and clear the fault. For almost two hours, Tansky flew the aircraft manually as they attempted to work out what was happening. At 15:47, the autopilot was reengaged, shortly after which Captain Thompson requested a diversion to Los Angeles International (LAX).

You might wonder why the pilots didn’t simply return to their point of origin as soon as a problem was experienced. With the information they had at the time, though, a straight return would have meant an overweight landing at high speed, which is always a risky situation. The airplane wasn’t uncontrollable at this point, and was flying fairly stable at altitude, so the decision was made to continue on their route, burn more fuel, and divert to LAX.

Conditions at LAX were favorable, and Thompson was in discussion with operations to get landing performance figures calculated for the MD-83. No emergency had been declared, so Alaska Airlines Flight 261 was being treated as a regular incoming flight. But the captain was still trying to figure out how to fix this problem.

The ‘two thumps’ that signalled the beginning of the end of Alaska Airlines Flight 261

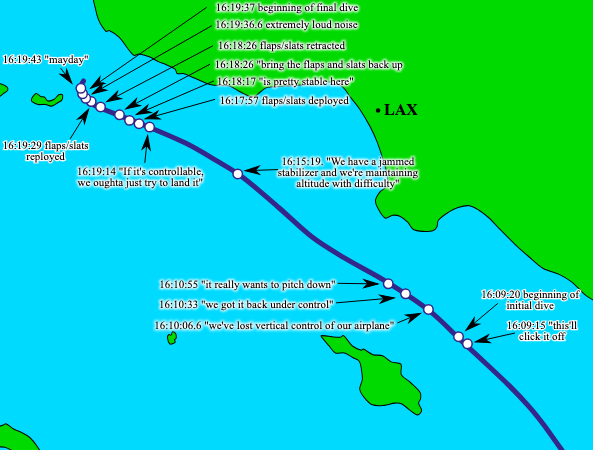

At 16:08, the cockpit voice recorder heard Captain Thompson saying, “I’m going to click it off. You got it?”

He was referring to the autopilot, which was disconnected around 10 seconds later. A loud clunk was heard, followed by two faint thumps from the back of the aircraft. Then the tone indicating the movement of the horizontal stabilizer sounded.

“Holy sh*t!” First Officer Tansky can be heard exclaiming as the aircraft pitched nose down and began to dive. The pilots fought the aircraft for over 80 seconds as it plunged towards the ground, and it took a combined effort of almost 130 pounds of force to pull the plane out of its dive.

At around 24,000 feet, the crew got the aircraft largely under control. They radioed air traffic control, advising that the situation had become much worse, and again talked to Alaska Airlines maintenance for advice. Los Angeles air traffic control handed the plane over to approach control in preparation for its arrival at LAX.

But Thompson knew the aircraft was in bad shape, and made the first of many heroic decisions that would save many lives that day. He declined the direct to the airport and requested vectors out over the bay to test out the landing configuration in a safe space, away from populated areas.

Having established the flaps were still working, and that the aircraft felt slightly more stable with flaps deployed, the pilots were ready to make their approach. Sadly, though, it was not to be.

‘At least upside down we’re flying’: The terrifying final moments of Alaska Airlines Flight 261

A series of faint thumps were heard on the cockpit voice recorder, along with First Officer Tansky asking, “You feel that?”. The aircraft’s horizontal stabilizer had pitched to 3.6 degrees down, making it even harder to maintain the aircraft’s altitude.

At 16:19, an awful noise of grinding and snapping metal was heard and the aircraft pitched forward violently. Again, the 88 passengers and crew entered a steep dive, hurtling towards the bay at more than 200 knots.

This time, instead of trying to pull out of the 70 degree dive, Captain Thompson pushed into it, rolling the aircraft over into an inverted position. He called out, “Push, push, push and roll,” with both pilots attempting to get the aircraft back onto the right keel.

Because of the roll, the pitch decreased from minus 70 degrees to 29 and then minus 9 degrees. They were now flying inverted over the bay. On the cockpit voice recorder, the two pilots can be heard shouting commands between each other to ‘kick rudder’ and ‘push the blue side up,” but despite their efforts, it was impossible to recover.

Some of Captain Thompson’s last words to his copilot were, “Got to get it over again, but at least upside down we’re flying.” However, these words were almost immediately followed by the sound of several compressor stalls and the right engine spooling down, as the extreme angle of oncoming air starved the engine inlets and caused the powerplants to fail.

At 16:21, Thompson could be heard saying “Ah, here we go…”

The aircraft impacted the Pacific Ocean at high speed, and all 88 souls on board were lost instantly.

Several other aircraft in the vicinity had witnessed what happened, and the crash site was quickly identified. At 700 feet, the water was too deep for Navy divers, so Naval ships brought sophisticated sonar equipment and deep-diving submersibles to aid in the underwater investigation. A flotilla of Coast Guard vessels, local fishing boats and lifeguard patrol craft combed the surface, collecting debris and body parts from the crash site.

While retrieving the remains of the victims was a key priority, it was also imperative that the teams located the so-called ‘black boxes’ from the aircraft – the cockpit voice recorder and the flight data recorder. Only then could investigators begin to figure out what had gone wrong.

What caused Alaska Airlines Flight 261 to crash?

Investigators were already suspecting that some fault in the tail of the airplane had contributed to the crash, so as well as the black boxes they were anxious to retrieve the rear empennage assembly. When it was brought up from the ocean floor, the investigators were shocked by what they found.

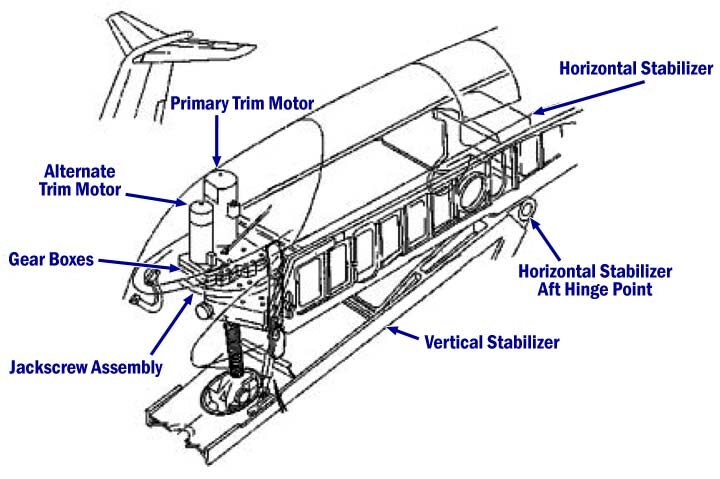

The MD-83 was a revised version of the popular DC-9, a rear-engined passenger jet with a distinctive T-tail design. This tail was made up of a vertical stabilizer with a rudder, to control yaw, and a horizontal stabilizer to control pitch. In the MD-83, its horizontal stabilizer is around 40 feet wide, and the entire wing moves up and down to alter the pitch of the aircraft.

The movement of this part is controlled by a ‘jackscrew’, held in place by an Acme nut. When the motor turns the screw, it moves up and down on the nut, causing motion of the horizontal stabilizer.

When the jackscrew assembly of Alaska Airlines Flight 261 was retrieved and inspected, the first thing investigators noticed was that the screw was no longer mated with the nut. This nut and screw assembly has very thick threads, so to find it separated was very unusual indeed.

Secondly, they noticed a piece of brass curled around the jackscrew like a slinky. It didn’t take long to realise this was the remnant of the threads inside the assembly, which held the jackscrew in place. With no thread left on the nut, the screw was turning but having no effect on the aircraft control.

Investigators also found the assembly was completely free of grease, with no lubricant at all on any of the moving parts. This would have exacerbated the wear on the nut as the parts rubbed together, ultimately causing the assembly to fail.

The jackscrew would have been moving freely for much of the flight, held in place by only a single retaining nut. That nut was never intended to support the loads generated by the airplane, and so grew weaker and weaker as the flight went on. Finally, it gave way entirely, allowing the horizontal stabilizer to move well beyond its aerodynamic limits, forcing the nose of the plane down.

It was clear that the jackscrew assembly had failed spectacularly, rendering the aircraft uncontrollable despite the best efforts of the heroic pilots. But why had this failsafe part ultimately failed?

To figure that out, investigators had to go back to basics. Back when the DC-9 was first certified, McDonnell Douglas had recommended lubricating the assembly every 300 to 350 flight hours. When the DC-9 became the MD-80, it was extended to 900 hours. Then, in 1996, a further revision included the lubrication requirement at every C check, which happened every 3,600 hours or 15 months, whichever came first.

When these changes came about, Alaska Airlines applied to extend the lubrication interval to eight months, which was actually more conservative than the recommendation. The FAA immediately approved this, but it was later found out that none of the original engineers at McDonnell Douglas had approved or even been consulted on the inclusion of lubrication at a C check. The task was simply bundled into other maintenance jobs without consideration for the impact.

Compounding this was Alaska Airlines’ misinterpretation of the requirements for checking the wear on the Acme nut. As the nut was made of softer metal than the screw, it would wear first, and needed to be checked at regular intervals. The manufacturer recommended every 30 months or 7,200 hours, whichever came first.

But Alaska Airlines had put it into their manuals that checks should be done every 30 months, without putting an hourly limit on it. Considering the busy flying schedule Alaska was operating at the time, the hours would be approaching 10,000 by the end of a 30-month period. N963AS was right at the end of its 30-month window when the accident occurred.

Following scrutiny of maintenance records at Alaska Airlines, discrepancies were quickly found in both their maintenance manual and how the maintenance work was actually being carried out at their various technical centers. On top of that, important management functions were unfilled at the airline, which had caused confusion about who was responsible for what.

Who was responsible for the crash of Alaska Airlines Flight 261?

The cause of the crash was determined to be a loss of control due to the in-flight failure of the horizontal stabilizer trim jackscrew assembly. Contributing to this was Alaska Airlines’ extended lubrication schedule and wear checks, which had both been approved by the FAA.

These two elements, combined with poorly executed lubrication practices, meant wear went undetected and ultimately led to the complete failure of the thread inside the Acme nut.

In all, 24 recommendations came out of the investigation. Some included giving clearer guidance to pilots on not repeating actions in checklists when it comes to the trim system, and not engaging autopilot when there are flight control problems.

But most of the recommendations were aimed at airlines and the FAA, and Alaska Airlines in particular. After the incident, the lubrication schedule on the MD-80 family was immediately changed to every 650 hours.

NTSB board member John J. Goglia wrote of the catastrophe: “This is a maintenance accident. Alaska Airlines’ maintenance and inspection of its horizontal stabilizer activation system was poorly conceived and woefully executed … NTSB has made several specific maintenance recommendations, some already accomplished, that will, if followed, prevent the recurrence of this particular accident. But maintenance, poorly done, will find a way to bite somewhere else.”

The NTSB’s final report concluded that Alaska Airlines’ improper maintenance practices were the primary cause of the crash, and the FAA’s failure to enforce proper oversight was a contributing factor.

Captain Ted Thompson and First Officer Bill Tansky were posthumously awarded the Air Line Pilots Association (ALPA) Gold Medal for Heroism, in recognition of their extraordinary airmanship and courageous efforts to save Alaska Airlines Flight 261.

This medal is the highest honor ALPA can award, given to pilots who have displayed exceptional skill and bravery in the face of extreme danger.