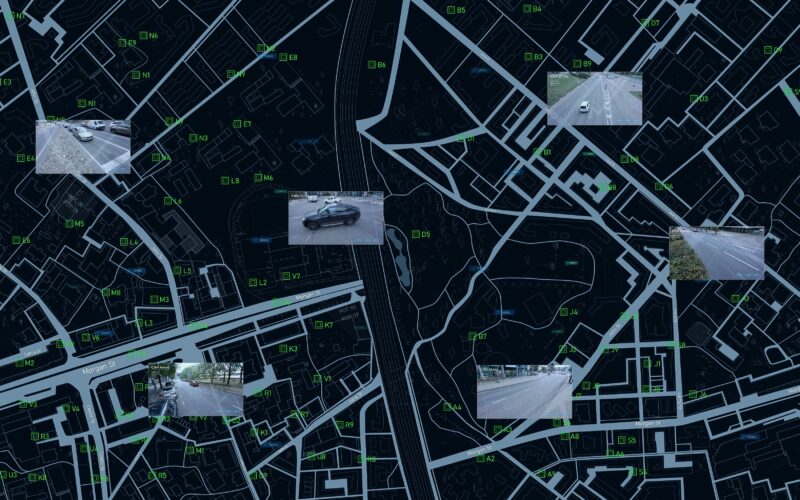

Once the sole domain of meteorologists and geographers, satellite imagery has become an increasingly useful tool for criminal investigations. Law enforcement agencies across the globe have taken advantage of the high-resolution images offered by satellite technology and are using greater quantities of such images than ever before to aid with investigations.

In criminal cases where evidence might be limited or challenging to obtain, satellite images can offer additional insight, helping to track movements, identify unusual activities in specific areas, or provide broader context to investigations.

For example, the United States National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) collects imagery from its own satellites but also acquires products from commercial vendors for use by the intelligence community, the military, and other agencies.

According to CBS News, the astonishing quality and resolution of current satellite photos could potentially fulfill 90% of US military intelligence needs.

Commercial satellite photographs are almost as good as those from military espionage satellites. Some companies provide satellite imagery with resolutions as high as 30 centimeters per pixel, allowing the identification of objects as small as 30 centimeters.

However, the use of commercial satellites for criminal investigations has raised questions about the ethical and legal implications of this technology.

The role of satellite surveillance in modern criminal investigations

Satellite imagery has proven its value in law enforcement, from cold cases to tracking criminal activities.

In June 2013, police officers in Grants Pass, Oregon, acted on a tip that Curtis W. Croft was illegally growing marijuana in his backyard. Police verified the claim using Google Earth, where a four-month-old satellite image revealed organized rows of plants on Croft’s property. The police executed a raid and confiscated 94 plants.

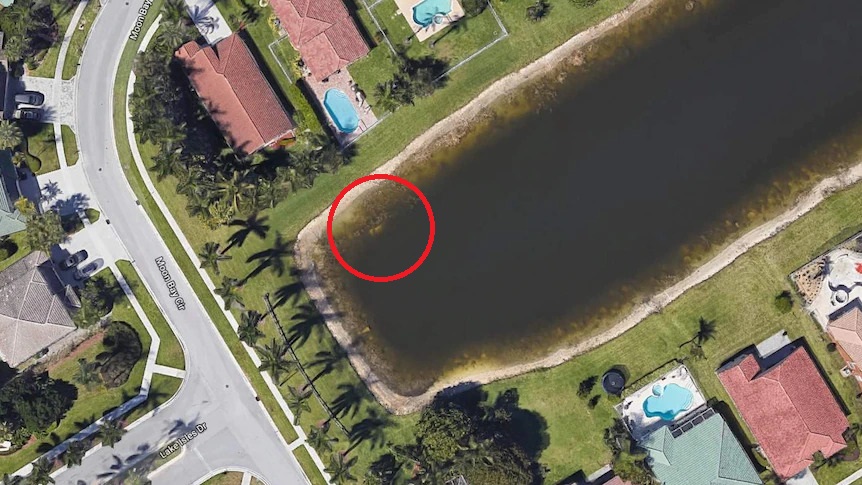

Another interesting example was the mysterious disappearance of William Moldt, who was reported missing on November 7, 1997, in Florida, US, after failing to return home following a night out.

While the case was cold for more than two decades, a breakthrough came on August 28, 2019, when a former area resident spotted a car submerged in a lake on Google Maps, prompting local authorities to investigate. The retrieved car contained skeletal remains later identified as belonging to Moldt.

The democratization of satellite imagery, enabled by advanced multi-modal sensors, ensures that every corner of the Earth is under constant surveillance. According to the satellite tracking website Orbiting Now, as of May 4, 2023, there are approximately 7,702 active satellites in various Earth orbits, 1,030 of which are for Earth observation.

Private sectors have capitalized on this prevalent technology, allowing customers to obtain specific data for an affordable price, starting from $20 for a single existing image and $175 for a single new image.

For example, disclosure requests submitted to the Japanese National Police Agency (NPA) showed that it had been utilizing commercial satellite imagery in criminal investigations since 2001, with 179 purchases made between 2016 to 2020, costing about 110 million yen ($781,000).

The global satellite imaging market size was valued at $3.27 billion in 2022 and is projected to reach $14.18 billion by 2030.

The double-edged sword of satellite surveillance

The danger is that almost anyone with a credit card and internet access can tap into the vast reservoir of commercially owned high-resolution data or even gather imagery with privately owned satellites.

On December 28, 2021, South Morning China Post reported that a small Chinese satellite, Beijing-3, was able to capture images of a large area around a US city in just 42 seconds. The images were clear enough to identify a military vehicle on the street and even determine the type of weapon it could be carrying.

Privacy advocates argue that constant surveillance from the sky infringes upon individual rights. Balancing security concerns with privacy rights remains a contentious issue.

“We like to think we have some privacy in our lives, that we can go places that we don’t necessarily want the government to know about,” said Jennifer Lynch, an attorney at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, an internet civil liberties group.

“What concerns me is, if all of those cameras get linked together at some point, and if we apply facial recognition on the back end, we’ll be able to track people wherever they go,” Lynch added.

According to a study published on the American Chemical Society website in 2020, the increased use of satellite imagery in criminal investigations and law enforcement highlights the need for updated regulations and policies to govern the use of this technology. Privacy rights are typically addressed nationally, but inconsistent policies and the global nature of satellites necessitate an international solution.

While the Outer Space Treaty of 1967 grants all states free access to space and promotes the principle of “open skies”, it does not specifically address the challenges posed by commercial satellites.

From cameras to satellites: a new frontier for privacy concerns

The application of satellite imagery for public security has been met with the same level of skepticism once faced by surveillance cameras.

The proven crime solving value of satellite imagery makes it likely that governments will continue to use commercial satellites as assets for public security. Meanwhile, commercial satellite companies will continue to profit from providing technological solutions.

While in the US, the government may not have jurisdiction over foreign satellites, it can certainly regulate how local companies and customers use imagery captured by satellites. If the use of such imagery by US companies infringes on the privacy rights of US citizens, the government has the authority to intervene.

Currently, satellites in the US are subject to some regulations. Companies wanting to launch and operate a satellite must secure a license from the Federal Communications Commission and approval from the International Telecommunications Union.

Other countries also regulate their satellites. For instance, in Europe, the General Data Protection Regulation may apply to any imaging system that could personally identify EU (European Union) citizens. Canada’s satellites are governed by the Remote Sensing Space Systems Act, while China and India limit publicly available data on Google Earth.

However, the increasing capabilities of satellites present lawmakers with a unique challenge. They must formulate responses to privacy concerns before technological advancements outpace regulatory efforts. This once-in-a-generation challenge requires careful consideration and international cooperation to ensure that the benefits of satellite technology are harnessed while protecting the rights of individuals.