Air travel has had the effect of liberating human beings. Distance and time no longer confine us as they did, and we are now capable of traveling pretty much wherever we want on the planet.

However, this freedom we enjoy today did not come about overnight.

Blood, sweat and tears have been shed across decades, lives even lost, so that we could travel the globe by plane.

Without planes travelling to faraway countries for a well-earned holiday, our options would be vastly limited.

If you wanted to visit relatives around the other side of the world, you’d have to prepare yourself for at least four days stuck on a boat.

So, who are the most influential figures from history that left an indelible mark on aviation and broadened our horizons?

AeroTime looks at nine aviation figures that we think certainly played their part.

Sir George Cayley

(Dec 27, 1773 – Dec 15, 1857)

British-born Sir George Cayley is often referred to as the ‘father of aviation’, a title that speaks volumes as to how highly regarded the 18th Century born aviator is.

According to the United States (US) Centennial of Flight Commission, Sir George was the first person to identify the four forces of flight – namely weight, lift, drag, and thrust.

In 1853, at a village in North Yorkshire, Sir George recorded the first flight of a fixed-wing aircraft that carried an adult.

According to an account by Sir George’s granddaughter, the glider traveled 900 feet before coming to a stop with a bump.

And who was the fearless pilot? A young coachman called John Appleby, who had been persuaded by the nearly 80-year-old Cayley to jump on board.

“About 100 years ago, an Englishman, Sir George Cayley, carried the science of flight to a point which it had never reached before and which it scarcely reached again during the last century.” Wilbur Wright said of Sir George in 1909.

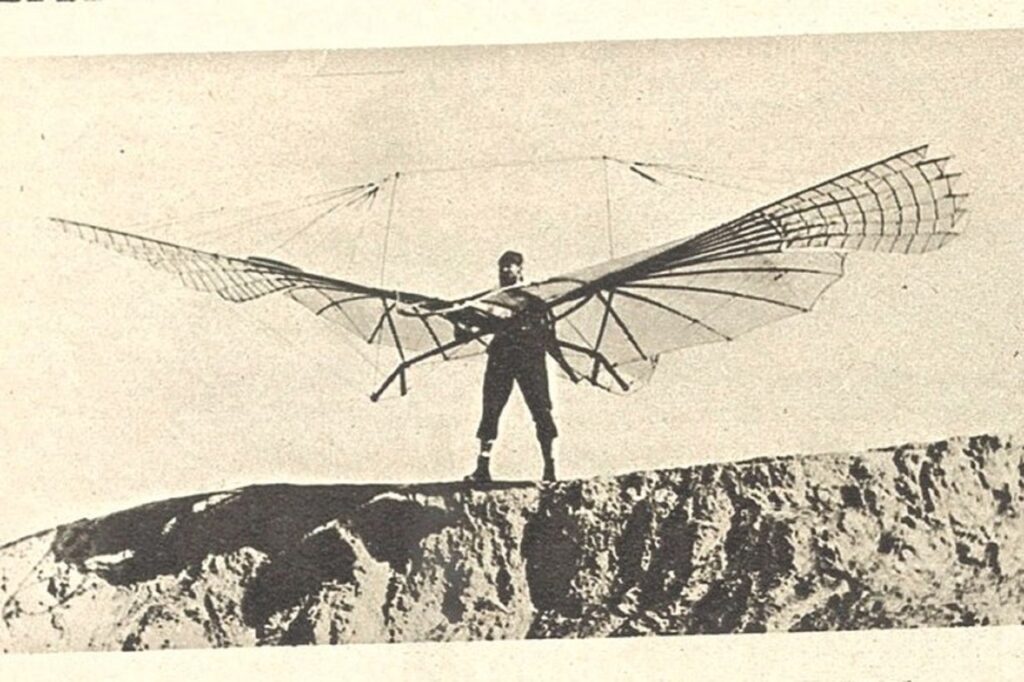

Otto Lilienthal

(May 23, 1848 – August 10, 1896)

Dubbed the ‘Flying Man’, Otto Lilienthal’s achievements in aviation would go on to influence pioneers such as the Wright brothers.

Lilienthal’s success came from flying gliders, which gradually built confidence among early aviators that ‘heavier than air’ aircraft flight was indeed possible.

The German innovator’s most famous flying machine was the Normal-Segelapparat, which had a wingspan of 6.7 meters.

Such was its success that the Normal-Segelapparat was sold to a number of buyers and subsequently became the first serial-produced aircraft in the world.

However, the aircraft was difficult to control as the pilot was forced to clasp the frame. This in turn limited the pilot’s ability to change direction, as it had to be achieved using only the bottom half of the body.

Sadly, after years of dedication to flying, a glider flight on August 9, 1896, caused Lilienthal’s death when the glider crashed.

“Of all the men who attacked the flying problem in the 19th century, Otto Lilienthal was easily the most important,” Wilbur Wright wrote in 1912.

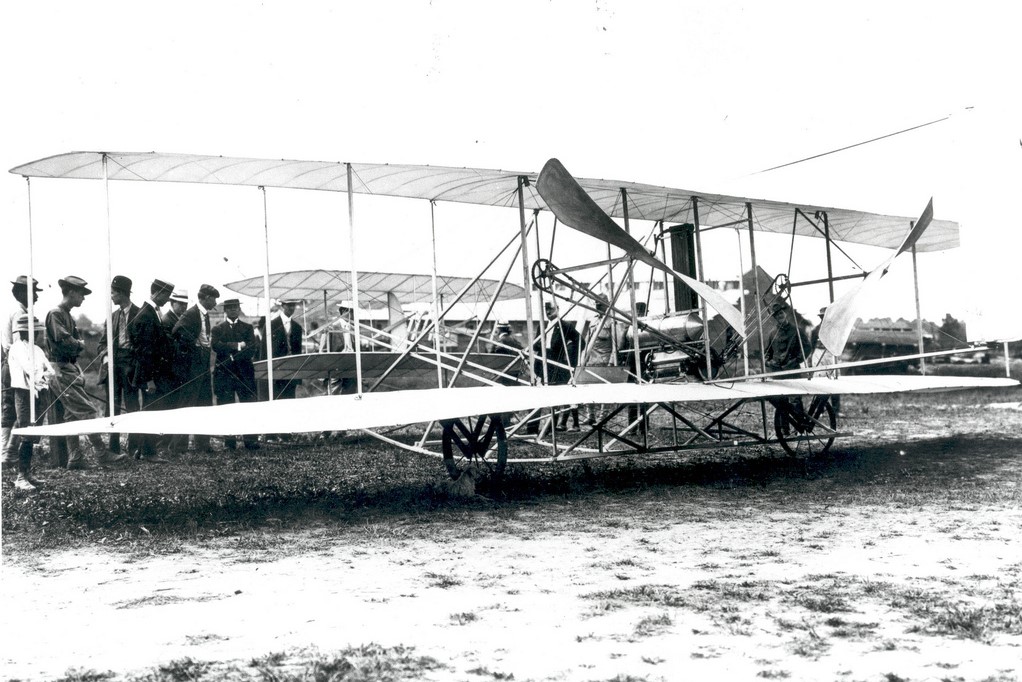

Wright brothers Orville and Wilbur

(August 19, 1871 – January 30, 1948) (April 16, 1867 – May 30, 1912)

Surely no other figures in the history of flight are as synonymous with aviation as the Wright brothers.

Both born in Dayton, Ohio in the US, Orville and Wilbur attended high school but left without qualifications.

Unperturbed, the Wright brothers moved into the printing business and even built their own printing press from scratch.

By 1892, the brothers had expanded by opening a bicycle repair and sales shop, with their own branded bikes available to buy.

However, as news began to spread through the US about European gliders and incredible aeronautical feats, the brothers decided to put their mechanical skills to use by building a plane.

As Orville and Wilbur started to explore the mathematics around flight, they made a key breakthrough by realizing that control of the aircraft was just as important as the wings and engines.

At first, the brothers started developing gliders and kites, a process which led to incredibly important discoveries and deepened their knowledge of aeronautics.

However, the holy grail was always a motor-operated plane.

On December 17, 1903, close to Kitty Hawk in North Carolina, a heavier-than-air powered and controlled aircraft called the Wright Flyer, manned by Orville, flew a distance of 20 feet in 12 seconds.

The short journey was the first time an engine-powered plane had achieved sustained flight and the reverberations from this moment would have a huge, wide-ranging impact.

In 1904 the Wrights’ second plane, Flyer II, went even further when both men flew for over five minutes in a circular pattern around a field.

In the years that followed, unfair doubts would spread about the brother’s achievement, with many people unable to fathom that flight was even possible.

Thankfully, though, as time passed Wilbur and Orville got the recognition that they deserved, and some of their aviation discoveries are still being used on aircraft today.

Alberto Santos-Dumont

(July 20, 1873 – July 23, 1932)

Alberto Santos-Dumont is regarded as a hero in his native Brazil and heralded as a pioneer of aviation around the world, even though he was ultimately beaten by the Wright brothers in achieving the first powered flight.

Santos-Dumont’s aviation journey started with airships. He was famed for his Santos-Dumont No. 6 airship, which he flew from Parc Saint Cloud to the Eiffel Tower in a celebrated Parisian race.

According to the American Physical Society (APS), after his airship escapades, Santos-Dumont turned his attention to heavier-than-air aircraft.

On October 23, 1906, at Bagatelle field in Paris, Santos-Dumont achieved Europe’s first officially observed powered flight by traveling around 80 feet.

A few weeks later, on November 12, 1906, he went even further and flew his aircraft a distance of 772 feet.

Following his flying marvels, in 1907 Santos-Dumont went on to design and build the Demoiselle, nicknamed ‘the grasshopper’.

The monoplane aircraft’s design was sold around the world and it is often viewed as the frontrunner for the modern light plane.

Bessie Coleman

January 26, 1892 – April 30, 1926

Bessie Coleman was the first woman of African American descent to earn her pilot’s license, an incredible achievement given the circumstances of the times in which she lived.

Born in Atlanta, Texas, on January 26, 1892, she spent much of her youth working in the cotton fields and studying at school.

But Coleman dreamt big and developed an interest in aviation. She applied to train as a pilot at American flight schools, only to be turned down because of her ethnicity and gender.

Her luck changed when her brothers returned from the First World War, and she was told that, in France, female pilots were not uncommon.

Buoyed by this revelation, Coleman saved her earnings and eventually travelled to France, where she was accepted at the Caudron Brothers’ School of Aviation in Le Crotoy.

On June 15, 1921, she finally achieved her life goal and was certified as a pilot by the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale.

She returned to the US with a spring in her step and secured a job as a stunt pilot. She was nicknamed ‘Brave Bessie’ and crowds flocked to watch her perform dazzling plane acrobatics.

On April 30, 1926, she was a passenger on a test flight when the pilot lost control. At just 34 years of age, Coleman fell from the plane and died.

Today, though, Coleman is heralded as an inspiration and a symbol of what people can achieve when the odds are stacked against them.

Frank Whittle

(June 1, 1907 – August 8, 1996)

Frank Whittle’s mathematical genius was spotted while he was working as an aircraft apprentice for the British Royal Air Force (RAF).

He was quickly elevated for officer training, and it was during this time he began to develop ideas for the world’s first turbojet engine.

Once he graduated, Whittle presented his idea to the UK’s Air Ministry, but he was met with knockbacks and a lack of enthusiasm.

In January 1930, though, encouraged by a flying officer named Pat Johnson who was formerly a patent examiner, Whittle had his vision of a turbojet engine officially patented.

On May 15, 1941, the first British jet-powered plane based on Whittle’s design took off from RAF Cranwell and flew for 17 minutes.

Only weeks before, the German’s own turbojet engine aircraft, Messerschmitt Me 262, had made its maiden flight.

Consequently, some have argued that German engineer Hans von Ohain was the true founder of the turbojet. However, Whittle’s decision to patent the idea in 1930 ensured that history has recognized him as the first.

“My interest in jet propulsion began in the fall of 1933 when I was in my seventh semester at Gottingen University,” Ohain said. “I didn’t know that many people before me had the same thought.”

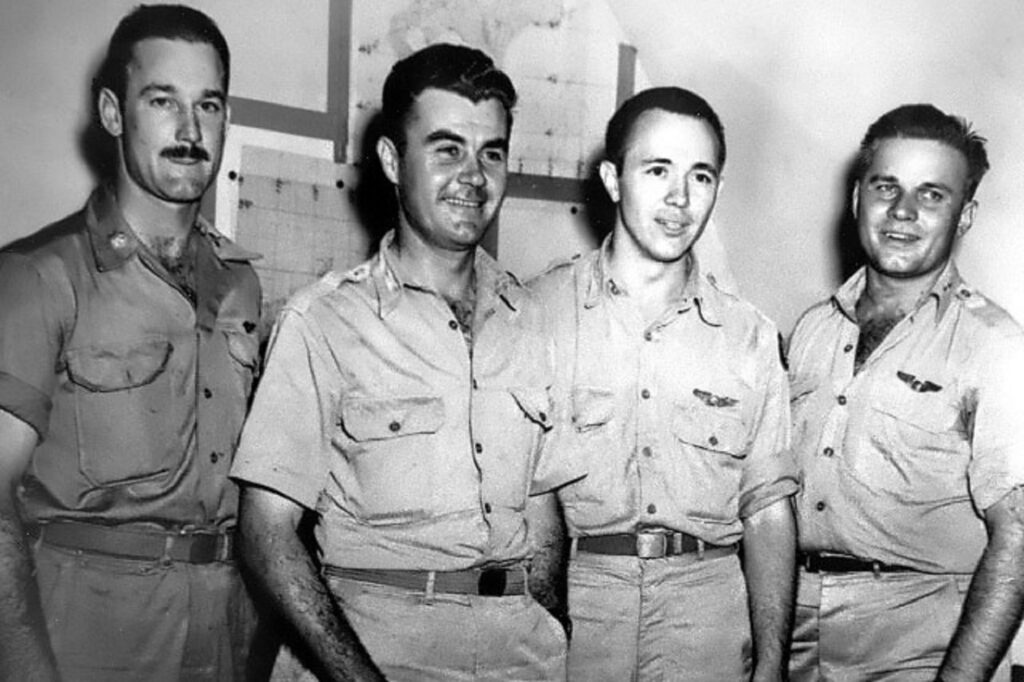

Paul Tibbets

(February 23, 1915 – November 1, 2007)

On August 6, 1945, during the Second World War, US Brigadier General Paul Tibbets was the aircraft captain of the B-29 Superfortress that dropped the atomic bomb on the Japanese city of Hiroshima.

The atomic weapon, dubbed ‘Little Boy’, dropped from the plane nicknamed Enola Gay after Tibbets’ mother, killed between 70,000 and 140,000 people.

Arguably the mission led by Tibbets was an exercise in cruelty on a colossal scale. Nevertheless, the bombing proved to be a monumental event that triggered the end of a devastating war.

In a 1989 interview, Tibbets said: “I made up my mind then that the morality of dropping that bomb was not my business. I was instructed to perform a military mission to drop the bomb. That was the thing that I was going to do the best of my ability,”

Tibbets added: “Morality, there is no such thing in warfare. I don’t care whether you are dropping atom bombs, or 100-pound bombs, or shooting a rifle. You have got to leave the moral issue out of it.”

Charles Yeager

(February 13, 1923 – December 7, 2020)

American Charles Elwood Yeager, known as Chuck, was a US Air Force officer who became the first pilot to break the speed of sound barrier.

At the time of achieving the feat, the aviation industry was unsure how an aircraft and the human body would respond to breaking the sound barrier.

So, when Yeager piloted the Bell X-1 rocket engine-powered aircraft on October 14, 1947, at Mach 1 speed, the Americans were entering unchartered territory.

Thankfully, Yeager did not vaporize when he broke the sound barrier. Instead, his achievement opened a doorway into a whole new era of flight.

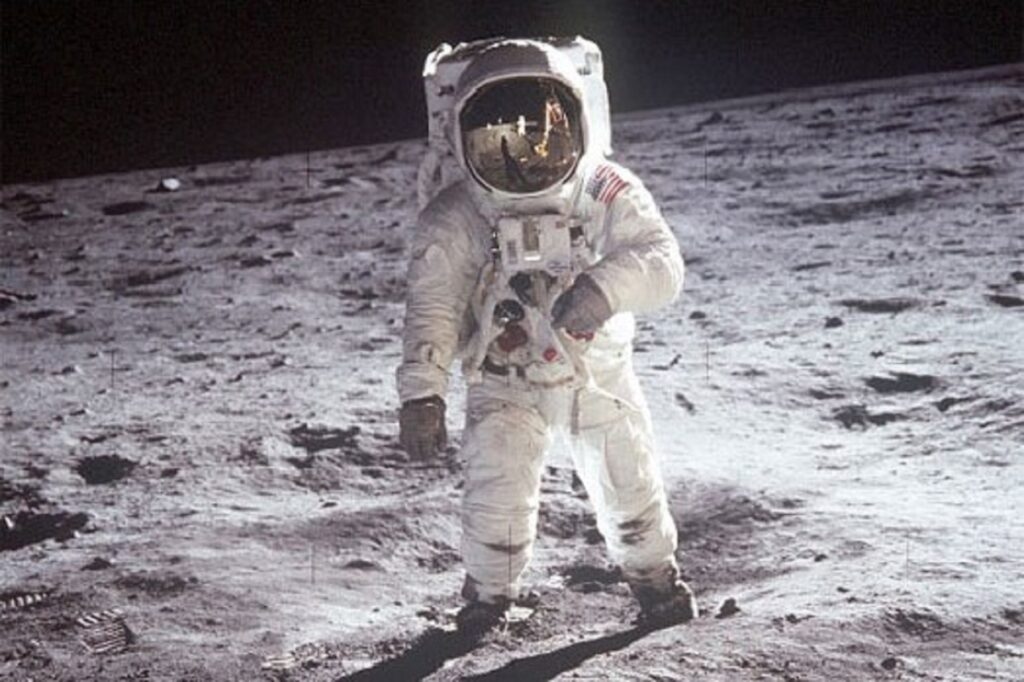

Neil Armstrong

(August 5, 1930 – August 25, 2012)

Neil Armstrong was a pilot who rose to become the first man to walk on the moon, thereby inspiring generations to learn how to fly.

Armstrong grew up in Ohio, where he developed a passion for flying. He gained his pilot’s license in 1947 when he was only 15 years old.

He subsequently began studying aeronautical engineering at Purdue University in Indiana. Then, during the Korean War, he flew fighter planes from the aircraft carrier USS Essex.

He joined the NASA Astronaut Corps in 1962 and made his first spaceflight in March 1966 as command pilot of Gemini 8, the first mission to link two spacecraft together in Earth orbit.

Three years later, on July 20, 1969, Armstrong reached the pinnacle of his career and made history when the Apollo 11 Lunar Module landed on the moon.

Armstrong was seen on television by millions around the world as he slowly lowered himself down a ladder onto the dusty surface.

Famously, he remarked: “That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.”

Who have we missed? Which other figures from the history of aviation deserve to make the AeroTime list?