For many, the start of January is seen as a brand-new start, a time to look to the future and shake off the troubles of the previous year.

The aviation industry is no exception.

After muddling its way through the challenges of the festive season, the first weeks of January are a time for the industry to gear up and focus on the 12 months ahead.

New routes, recruitment, more ambitious plane manufacturing numbers and the profitable summer season might seem within touching distance.

Unfortunately, plans have a habit of not always turning out how we hoped.

The passengers and crew onboard Japan Airlines (JAL) Flight 516 on January 2, 2024, and Alaska Airlines Flight 1282 on January 5, 2024, know that more than most.

In less than one week, 367 passengers aboard an Airbus A350 and 171 passengers on a Boeing 737 MAX 9 discovered exactly what it means to be in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Both flights will forever be linked in aviation history as narrowly averted large-scale disasters occurring just four days apart.

Tragically, five staff members from the Japan Coast Guard onboard the Dash 8 that was struck by Flight 516 in Tokyo were not so lucky and lost their lives.

Just how these events unfolded still remains to be determined, and the lessons that can be learned are only just beginning to surface.

But what is clear is how much more catastrophic the first week of January 2024 could have been if events had turned out differently.

January 2, 2024 – Japan Airlines Flight 516

On January 2, 2024, a Japan Airlines Airbus A350-900 left New Chitose Airport (CTS) at 4:27 pm local time for a short flight to Tokyo Haneda Airport (HND).

The Airbus A350 widebody aircraft, registered JA13XJ, was first flown on September 20, 2021, and delivered to Japan Airlines on November 10, 2021, so it was a relatively young plane.

After an uneventful flight, the A350 approached HND, with those onboard unaware of the events that would unfold as the plane touched down.

JAL516便(推定) 新千歳→東京/羽田

— 田中 (@tshinfuku1115) January 2, 2024

羽田空港C滑走路で

着陸時に海上保安庁機と衝突

乗客はスロープを使って避難

けが人などの情報は確認中

(JNN) pic.twitter.com/MrpXH0g6fh

At the airport, a De Havilland Canada DHC-8-315Q was taxiing in preparation to take off. Flown by the Japanese Coast Guard, it was being used to deliver aid to the region of Japan hit by an earthquake on January 1, 2023.

After the A350 was given permission to land on runway 34R, the large jet came into land, but the Coast Guard plane had broken its holding position and was now in the path of the incoming aircraft.

As the A350 landed the two planes collided, with the Dash 8 taking most of the impact.

As the Coast Guard plane exploded, the A350 continued down the runway and a fire began to develop on the aircraft’s exterior.

The Japan Airlines pilots only realized that the left engine was on fire when they were informed by a flight attendant.

Evacuation of the plane was initiated, but problems with the intercom, and the fact that only three of eight emergency exits were safe to use, made the process much more challenging.

However, 18 minutes after the impact, all passengers and crew had escaped the plane, which by that time was engulfed in flames.

The Coast Guard pilot managed to escape from the Dash 8, but tragically all five other people on board were killed.

January 5, 2024, – Alaska Airlines Flight 1282

On January 5, 2024, Alaska Airlines Flight 1282 took off from Portland International Airport (PDX), Oregan in the United States (US) at 5.07pm local time.

Onboard the circa two-hour flight to Ontario International Airport (ONT) were 171 passengers and six crew members.

The Boeing 737 MAX 9, registered as N704AL, was fresh off the production line. The jet had been delivered to Alaska Airlines in October 2023 and only entered service on November 11, 2023.

As the 737-9 began to climb after taking off from PDX, it was travelling at around 440 miles per hour, nearly 15,000 feet up in the air.

Alaska Airlines Flight 1282 made an emergency landing in Portland, Oregon on January 5, after an issue with pressurization. A panel of the fuselage, including the panel’s window, popped off shortly after takeoff.

— Massimo (@Rainmaker1973) January 6, 2024

[📹 vy.covers]https://t.co/VRzA10AilE

According to the flight data recorder, at 5.12pm, as Flight 1282 passed 14,830 feet, a plug door positioned between the wing and the rear cabin exit separated from the fuselage.

Passengers have since described the moment as an explosion followed by a rapid decompression that triggered oxygen masks to deploy.

“We just depressurized, we’re declaring an emergency. We need to descend down to 10,000. We just need to depressurize, and we need to return back to Portland,” the pilot told air traffic control.

Reaching a maximum altitude of 16,320 feet, the 737-9 began to descend and fell below 10,000 feet around four minutes later.

During the rapid decompression inside the cabin, the cockpit door flung open and many items such as mobile phones and pilot headsets were lost.

Footage taken from inside the plane at the time showed the effects of air rushing through the cabin, but passengers appeared calm despite the extraordinary events.

At 5.36pm, the 737 MAX 9 landed back on runway 28L at PDX and emergency responders entered the aircraft to check on the passengers.

Several guests onboard had injuries that required medical attention, but all passengers were subsequently cleared to return home.

The aftermath

News of both the JAL and Alaska Airlines incidents quickly caught the attention of the world’s media as aviation experts tried to unpick what had happened.

Japan Airlines – Airbus A350

Footage of the A350 on fire at HND brought home how lucky the passengers had been, but concern was expressed over the ferocity with which the aircraft burned.

When it was confirmed that all 367 passengers and 12 crew members had escaped the aircraft, the news was met with astonishment.

According to JAL, the full evacuation of the aircraft was completed in 18 minutes from the time the planes collided.

Airworthiness certification standards stipulate that, during an emergency, all passengers on a modern aircraft need to be able to evacuate an aircraft within 90 seconds.

So, under those rules, despite huge praise for crew members on the JAL flight, was the evacuation a failure?

Working under extremely difficult conditions, crew members did the best they could, and their efforts saved everyone onboard the plane.

A faulty intercom system, limited available emergency exits and a cabin filling with smoke reducing visibility: these factors all worked against the crew, but thankfully they rose to the occasion.

The passengers also deservedly received much praise following the incident.

Footage taken within the cabin showed that passengers remained incredibly calm throughout. Crucially, no-one appeared to leave the plane with hand luggage. Doing so may have increased the evacuation time and general sense of panic.

There has also been much discussion since the incident about whether the carbon-composite material used to make the plane helped or hindered the evacuation.

According to reports, it took airport firefighters six hours to extinguish the fire completely, but at the same time the carbon-composite material used in the fuselage undoubtably kept passengers safe

Safety consultant John Cox told the Associated Press: “This is the most catastrophic composite-airplane fire that I can think of. On the other hand, that fuselage protected (passengers) from a really horrific fire — it did not burn through for some period of time and let everybody get out.”

Airbus and many other companies working in aviation will no doubt be keen to analyze any data that becomes available about how the fire affected the carbon-composite material used on the A350.

Alaska Airlines – Boeing 737 MAX 9

So far, the Alaska Airlines plug door blowout has impacted the aviation industry far more than the JAL crash.

Following the incident, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) issued an Emergency Airworthiness Directive (EAD) for inspections on 171 737-9 jets worldwide configured with the plug door matching Flight 1282.

As well as impacting Alaska planes, United Airlines grounded all its 737-9 aircraft, after initially advising that only a select number of aircraft would be inspected.

Turkish Airlines grounded four of its 737 MAX 9s, while the Panama national flag-carrier, Copa Airlines confirmed it had grounded 21 737-9s and the Mexican airline AeroMexico announced it all its MAX 9s will undergo inspections.

The European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) has confirmed that it has adopted the FAA’s EAD, despite admitting that, to its knowledge, “and also on the basis of statements from the FAA and Boeing, no airline in an EASA Member State currently operates an aircraft in the relevant configuration”.

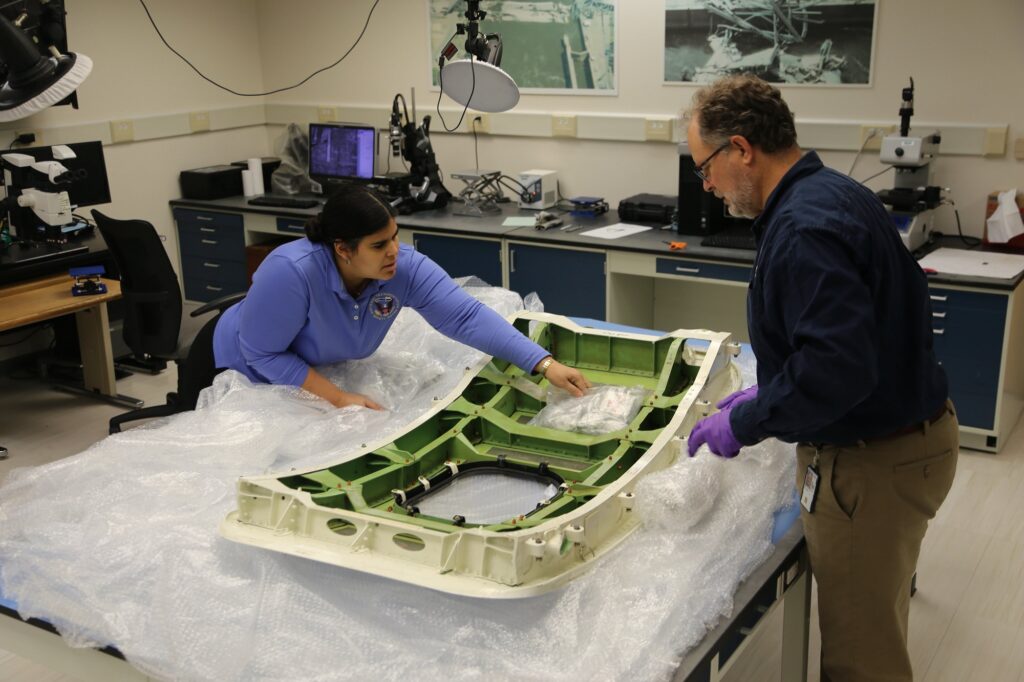

In the days that followed the Alaska incident, the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) confirmed that issues had been found with the plug door mechanism which should have held it in place.

Clint Crookshanks, Aerospace engineer at NTSB, said: “The exam to date has shown that the door in fact did translate upward. All 12 stops became disengaged, allowing [the door plug] to blow out of the fuselage. We found that both guide tracks on the plug were fractured.”

Crookshanks added: “We have not yet recovered the four bolts that restrain it from its vertical movement, and we have not yet determined if they existed there. That will be determined when we take the door plug to our lab in Washington DC.”

Pressure on Boeing and its assembly line processes quickly began to build. On January 10, 2024, Boeing CEO Dave Calhoun told CNBC that a “quality escape” was at the heart of the 737-9 blowout, indicating that something was not built correctly, or else was missed, which had compromised the plane’s safety.

“What broke down in our gauntlet of inspections? What broke down in the original work that allowed for that escape to happen?” Calhoun said.

On January 11, 2024, the FAA announced that it was also launching an official investigation into Boeing, to establish whether the plane-maker complied with federal regulations and the aviation agency’s “approved quality system” during production.

The following day, the government agency said that it would conduct an audit involving the 737-9 MAX production line and its suppliers to “evaluate Boeing’s compliance with its approved quality procedures” and explore the use of an independent third party to oversee Boeing’s inspections and its quality system.

On January 25, 2024, the FAA finally approved a “thorough inspection” and maintenance process, to be completed on each of the 171 grounded 737-9 and several have since begun to return to service.

However, despite the breakthrough it’s clear that the consequences for Boeing and the aviation industry will continue to reverberate.

While authorizing the final inspections, the FAA said in a statement that it will not grant any manufacturing expansion of the MAX family aircraft, including the 737-9 MAX, and will increase oversight of Boeing’s production lines.

“Let me be clear: This won’t be back to business as usual for Boeing. We will not agree to any request from Boeing for an expansion in production or approve additional production lines for the 737 MAX until we are satisfied that the quality control issues uncovered during this process are resolved,” Michael Whitaker, head of the FAA, said.

And the problems for Boeing continue to mount, with Alaska Airlines indicating that it wants Boeing to reimburse $150 million in losses caused by the grounding of its planes.

But perhaps the biggest consequence of the Alaska Airlines plug door blowout has been the damage to Boeing’s reputation.

“Until this incident, we were happy with the Max.” said Alaska Airlines CEO Ben Minicucci said on January 25, 2024, “But we are going to hold Boeing’s feet to the fire to make sure that we get good airplanes out of that factory.”

The problem now facing Boeing is that the Alaska CEO won’t be alone in this, and that many of the planemaker’s customers will inevitably be making similar demands.

The cause

The Japan Transport Safety Board and the NTSB are continuing to investigate what caused both incidents in the first week of January 2024, so no official conclusions have yet been reached.

However, possible causes began to surface almost immediately after the two events.

Japan Airlines

The JAL A350 investigation will be paying close attention to communications between air traffic controllers and the flight crews of both the Airbus A350 and Dash 8 Coast Guard plane.

On January 3, 2024, the Japanese Transport Ministry released a transcript of conversations between air traffic controllers and the two aircraft moments before they collided.

The transcript suggested that the Coast Guard aircraft had not been cleared to enter the runway while it also confirmed that the Airbus A350 was given permission to land on Runway C.

Tragic incident at Haneda airport as Japan Airlines Airbus A-350, collided a Coast Guard plane. The commercial airplane, engulfed in flames but all passengers were safely evacuated pic.twitter.com/veDMFx5FWt

— Science girl (@gunsnrosesgirl3) January 2, 2024

According to the transcript, several seconds after the Japan Airlines jet was given the go-ahead to land, the Coast Guard plane was told to proceed to a holding point on a taxiway, an instruction the pilot repeated back.

But around two minutes later, the two aircraft collided on the runway as the A350 landed.

However, according to a Coast Guard official, the captain said that he had entered the runway after receiving permission.

Another part of the investigation is certain to examine why the flight crew of the JAL flight did not see the Coast Guard plane on the runway.

Alaska Airlines

It has become increasingly clear that, during the assembly of the Alaska Airlines 737-9, something went wrong.

Calhoun even acknowledged at a company town hall meeting that a “mistake” had led to the plug door blowout.

But it’s still not known where or when that mistake was made.

On January 24, 2024, the Seattle Times reported that it had been informed by someone familiar with the Boeing production line that the plug door which separated from the Alaska Airlines jet was removed from the fuselage during the final assembly process for repair and not reinstalled correctly.

This follows another whistleblower claiming in the comments section of an article by the Leeham News that four bolts designed to prevent a plug door sliding up were “not installed when Boeing delivered the airplane”.

The Air Current expanded on this issue in an article which reported that the plug door on the Alaska 737-9 was opened to allow Spirt AeroSystems engineers access to five rivets that had not been installed correctly.

To open or remove the plug door, the four bolts would have been removed. Following the plug door blow out on January 5, 2024, the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) said that these bolts could not be located.

“Where are the bolts? Probably sitting forgotten and unlabeled (because there is no formal record number to label them with) on a work-in-progress bench, unless someone already tossed them in the scrap bin to tidy up,” the whistleblower commented.

How far from catastrophe were both incidents?

Whether a tragic event is a catastrophe is not judged on whether a plane was destroyed or if a company’s share prices dropped, they are simply judged on the loss of human life and injury.

As such, the Japan Airlines Flight 516 crash was indeed a catastrophe.

Five people who were serving their country while trying to provide aid to victims of an earthquake were killed in dreadful circumstances.

But the fire that engulfed the A350 could undoubtedly have been so much worse, and the 379 people on board were lucky to escape with their lives. In that respect, an even greater tragedy was averted.

When the plug door separated from the fuselage of Alaska Airlines Flight 1282 the 737 MAX 9 was approaching an altitude of 16,000 feet.

Passengers and crew were all strapped in, and no one was walking around the cabin.

If the aircraft had suffered a plug door blowout after it reached cruising altitude, it could have concluded very differently.

Even at just below 16,000 feet, phones, seat attachments and clothes were ripped away by the cabin’s sudden depressurization.

NTSB Chair Jennifer Homendy has admitted that the incident would have been much worse had the 737-9 reached 35,000 feet.

“We could have ended up with something so much more tragic,” Homendy said.