Hypersonic weapons have emerged in the collective consciousness as a significant development in modern warfare, offering unprecedented speed and maneuverability.

From a purely physical point of view, however, hypersonic weapons are not new. The first man-made vehicle to have traveled at such speed was the Bumper sounding rocket. Based on a German-made V-2 ballistic missile, it reached 5,150 miles (about 8,300 kilometers) per hour during a flight test on February 24, 1949.

From then on, ballistic missiles such as the Soviet-made Scud have routinely crossed the Mach 5 bar since the 1960s, and have even reached up to Mach 20 in the case of intercontinental missiles.

Yet for the past decade, and even more so since the outbreak of the invasion of Ukraine by Russia, hypersonic weapons are regularly featured in headlines as the holy grail of the aerospace and defense industry.

With such a well-established concept, why are hypersonic weapons currently rising to prominence in the military discourse? Here is a comprehensive guide exploring both the history and the current significance of hypersonic weapons.

What is a hypersonic weapon?

A hypersonic weapon is a type of weapon system that travels at extremely high speeds, typically exceeding Mach 5 (five times the speed of sound). Such speeds enable these platforms to travel long distances much faster than conventional weapons and make them difficult for air defense systems to intercept.

However, the high speeds achieved by hypersonic weapons present significant technical challenges. The intense heat generated by air friction, known as thermal heating, poses a major hurdle for their design and structural integrity. Thus, hypersonic weapons not only require innovation in propulsion, but also in material capable of sustaining such speeds. Manufacturers sometimes refer to this phenomenon as the “heat barrier” drawing a parallel to the sound barrier that marked a significant milestone in weapon technology.

Until now, hypersonic weapons were limited to ballistic missiles, with a fully predictable high-altitude parabolic trajectory making them vulnerable to long-range detection and interception. These weapons also require advanced guidance and control systems to maintain stability and accuracy during high-speed flights.

Though they entered service more recently, the same limitations can be extended to hypersonic air-launched ballistic missiles such as the Kh-47M2 Kinzhal.

Russia advertises the Kinzhal as a hypersonic missile that can be carried by the Tu-22M bomber or the MiG-31 heavy interceptor. According to official Russian sources, it has a top speed of either Mach 10 or Mach 12 (10 or 12 times the speed of sound). The Kinzhal is based on the first stage of the 9K720 Iskander ground-launched ballistic missile, with the addition of a booster.

Kh-47 hypersonic missiles launched by MiG-31 heavy interceptors were used in Russia’s invasion of Ukraine to target key cities. One Kh-47 hypersonic missile was intercepted over Kyiv by the Patriot system shortly after its deployment on May 4, 2023, as confirmed by the spokesman of the US Department of Defense, proving to the world that speed alone was not enough.

Maneuverable reentry vehicles (MaRV), a type of warhead for ballistic missiles capable of maneuvering and changing its trajectory when re-entering the atmosphere for terminal guidance, changed the game slightly. Such warheads can be found on the Chinese DF21 anti-ship ballistic missile (ASBM).

However, the trajectory of these weapons remains predictable during their mid-course phase, allowing long-range detection with surface radar and interception by anti-ballistic missile systems.

The new hypersonic era

So why are hypersonic weapons currently in the spotlight? In recent years, hypersonic weapons have taken center stage in the realm of modern warfare technology, drawing significant attention for their supposed game-changing capabilities.

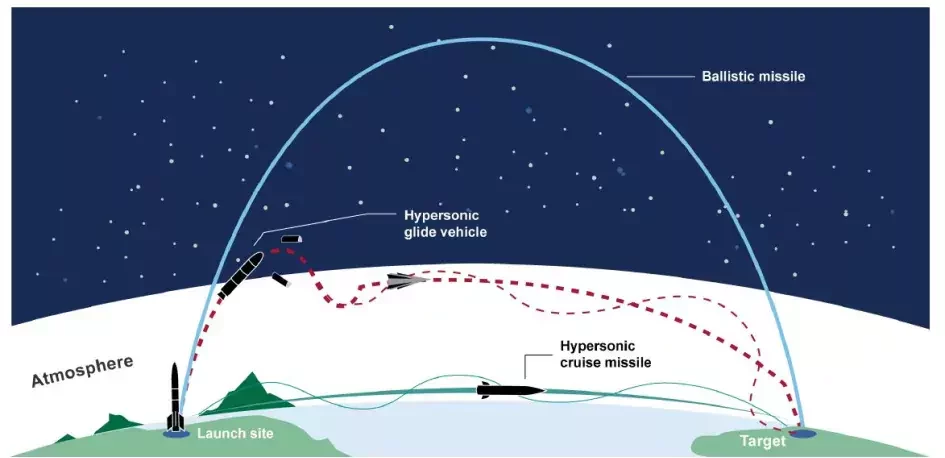

Two types of hypersonic weapons are currently under development: hypersonic cruise missiles (HCM) and hypersonic gliding vehicles (HGV).

Hypersonic cruise missiles are a faster version of existing cruise missile designs, using an airbreathing scramjet to reach hypersonic speeds in the atmosphere.

Hypersonic gliding vehicles use a boost-glide launch system: first, a rocket propels the weapon to the edge of space before the payload glides back into the atmosphere to its target at hypersonic speed. The glider uses a non-ballistic trajectory known as a skip reentry or a ballistic coast. During this maneuver, the vehicle enters and leaves the high atmosphere once or several times, extending the range and allowing for a lower flight altitude than a ballistic trajectory, thus limiting detection and path prediction.

These two types of weapons are designed to operate within a flight domain strategically positioned between endo-atmospheric and exo-atmospheric altitude, a sweet spot where existing defense systems scarcely operate.

Indeed, contemporary defense systems are designed to function within two primary altitude ranges: below 30 km (SM2, PAC3, Aster, S-400) and above 50 km, covering both endo-atmospheric and exo-atmospheric regions (ThAAD, SM3, Arrow 3, A-135).

These new hypersonic weapons also remain under the radar horizon until the final phase of their flight by maintaining a more horizontal trajectory, leaving limited time for terminal air defenses to react. Combined with the capacity to maneuver throughout the majority of their flight, this makes target path prediction, and thus interception, particularly challenging.

Do hypersonic weapons already exist?

Hypersonic weapons have garnered significant attention since Russia’s use of Kinzhal missiles during the conflict in Ukraine. However, the origins of this renewed interest in hypersonic capabilities can be traced back to a time well before the war.

Russia was the first country to claim to have fielded hypersonic weapons, an announcement that has garnered significant attention from the international defense community. In a lengthy parliamentary address on March 1, 2018, Russian President Vladimir Putin unveiled a range of new weapons aimed at countering NATO’s anti-missile systems and strengthening Russia’s nuclear deterrent capabilities. Among those weapons were hypersonic missiles, which he noted all leading militaries around the world “are known to be actively developing”.

In December 2019, Russia conducted the first known combat deployment of the Avangard system at a regiment of the 13th Red Banner Rocket Division of Dombarovsk, in the Orenburg region. The Avangard is a hypersonic boost-glide system designed to be mounted on intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs). It is intended to carry either a conventional payload or a nuclear warhead, making it a strategic deterrent in Russia’s military capabilities.

Another notable hypersonic weapon in Russia’s inventory is the 3M22 Zircon, a scramjet-powered anti-ship cruise missile capable of reaching speeds of up to Mach 9 (over 11,000 kilometers per hour). This weapon was fielded by Russia during a significant moment in international relations: mere days before the invasion of Ukraine.

On January 4, 2023, the Russian frigate Admiral Gorshkov re-entered service at the naval base of Severomorsk in Murmansk during a ceremony attended by Russian President Vladimir Putin and Russian Defense Minister Sergey Shoygu. The frigate had just undergone a one-month operation to arm it with 16 vertical launch system cells capable of launching 3M22 Zircon missiles.

“The ship is equipped with the latest hypersonic missile system,” Putin said during a broadcast ahead of the voyage. “I am sure that such powerful weapons will reliably protect Russia from potential external threats.”

On August 14, 2023, Alexei Rakhmanov, chief executive officer of Russia’s United Shipbuilding Corporation, revealed that the upcoming Yasen M-class nuclear submarines would be equipped with Zircon hypersonic missiles.

India also joined the hypersonic race by partnering with Russia in 2008 to develop the BrahMos-II, a hypersonic variant of the existing BrahMos supersonic cruise missile based on the Russian P-800 Oniks. However, no information has transpired since the beginning of the invasion of Ukraine.

While China’s specific achievements and advancements in hypersonic technologies are not as rigorously disclosed, it is widely acknowledged that the country has been actively pursuing the development of hypersonic weapons.

In 2019, the DF-17, which combines a ballistic missile with a hypersonic glide vehicle, the DF-ZF, appeared for the first time in a parade with China’s People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force.

In May 2023, the Chinese authorities made public the results of a simulated wargame in which they claim to have destroyed the US Navy nuclear-powered aircraft carrier USS Gerald R. Ford using 24 hypersonic anti-ship ballistic missiles. These were likely ship-launched YJ-21 missiles arming the Type 055 destroyer. While the outcomes of this simulation hold limited tactical significance, they highlight the prominent role that hypersonic weapons have assumed within the global defense discourse.

The same month, China also announced the successful completion of the JF-22 wind tunnel. The wind tunnel located in the Huairou District in northern Beijing is reportedly able to simulate flights of up to 10 kilometers per second or 30 times the speed of sound, making it the fastest in the world according to China’s Institute of Mechanics, its operator.

Unlike most other existing facilities that use mechanical compressors to generate high-speed airflow, the 265-meter-long wind tunnel relies on chemical explosions.

Officially, the facility will support the development of a space-to-earth shuttle system. But the tunnel may also be used for developing hypersonic weapons for Beijing.

In contrast, the United States experienced several setbacks in its hypersonic weapon development. Two programs have already been canceled. In February 2020, the Hypersonic Conventional Strike Weapon (HCSW), was canceled due to budget constraints. In March 2023, the decision was made to discontinue the development of the AGM-183 ARRW, a boost-glide weapon project undertaken by Lockheed Martin, which faced setbacks and multiple failed tests.

Currently, the United States is exclusively focused on pursuing a single hypersonic weapon concept program. In June 2019, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) and the United States Air Force initiated a competition, called the Hypersonic Air-breathing Weapon Concept (HAWC), in which Raytheon and Lockheed concurrently developed a scramjet-powered weapon capable of reaching speeds greater than Mach 5 (over 6,000 kilometers per hour).

In September 2022, Raytheon in collaboration with Northrop Grumman, its partner during the HAWC program, was awarded the Hypersonic Attack Cruise Missile (HACM) to design an operational hypersonic scramjet-powered weapon based on their previous research. In July 2023, the duo received an additional $81 million contract from DARPA to conduct additional HAWC test flights.

Japan also plans to develop hypersonic weapons. On July 24, 2022, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) successfully conducted the first flight test of a homegrown scramjet engine, reaching hypersonic speeds during descent.

In its annual budget request published on August 31, 2022, the Japanese Ministry of Defense said it would fund the development of hypersonic guided missiles to bolster its stand-off defense capability against threats posed by China and North Korea. In June 2023, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries received two contracts from the ministry, one to conduct hypersonic weapons research and another to develop the Hyper Velocity Gliding Projectile (HVGP), intended for deployment by 2026.

Finally, France is also developing both types of hypersonic missiles. The Direction générale de l’Armement (DGA), the French procurement and technology agency carried out the inaugural test firing of a sounding rocket carrying the V-MAX hypersonic glider demonstrator on June 26, 2023.

The successor to the ASMP missile, the airborne component of the French nuclear deterrent, will also be a scramjet-powered hypersonic cruise missile. Dubbed ASN4G (Air-Sol Nucléaire de 4ème Génération), it should be operational by 2035.

The invincibility of hypersonic weapons: myth or reality?

Warfare has witnessed paradigm shifts in weapon technology; each era being characterized by a dominant ‘Wunderwaffe’ (or wonder weapon.) And among all dimensions of modern conflicts, aerospace fostered much hope from leaders looking to possess a weapon so unilaterally powerful that it would deter any aggression.

As the Second World War was coming to an end, jet fighters revolutionized aerial combat and influenced subsequent generations of combat aircraft. Then in the late stages of the Cold War, passive stealth aircraft such as the F-117 Nighthawk and the B-2 Spirit emerged as a game-changing technology.

The landscape temporarily changed with the onset of counter-insurgency wars in the 1990s and 2000s, where superpowers faced asymmetric threats, often requiring low-tech solutions to address the challenges posed by guerilla warfare and terrorism.

However, the current geopolitical climate, marked by the resurgence of great power competition, has brought forth a new era where hypersonic weapons are emerging as the novelty weapons of high-intensity conflict.

While wonder weapons can indeed wield a significant impact on the battlefield and serve as potent propaganda tools, the annals of history consistently demonstrate that these armaments seldom live up to the mythical prowess assigned to them and fall short of providing a guaranteed victory in a conflict.

The introduction of the German Messerschmitt Me 262 fighter jet showcased unprecedented speed and performance, but it did not single-handedly determine the outcome of the war. And when on the night of March 27, 1999, a Serbian-operated SA-3 Goa surface-to-air missile managed to lock onto and strike an F-117 Nighthawk, it demonstrated that stealth technology was by no means an infallible cloak of invisibility.

As hypersonic weapons have garnered increased attention, efforts to develop countermeasures against these advanced technologies have been underway, in the classic ‘race’ between offense and defense.

Early warning systems and threat path prediction will be crucial for implementing an effective defense strategy against hypersonic weapons.

Space-based sensors can help overcome radar horizon limitations, extending the reach of detection capabilities and giving more time to implement an interception strategy.

Additionally, the integration of artificial intelligence and advanced algorithms can optimize the prediction of interception areas, challenging the maneuverability of these weapons.

Finally, the maturation of hypersonic propulsion itself should contribute to the development of more capable interceptor missiles.