December 21 marks a tragic milestone in aviation history. On this day in 1988, a Pan American (Pan Am) Boeing 747 flying from London to New York exploded over a small town in Scotland when a bomb hidden onboard detonated. The aircraft broke apart and subsequently crashed with the loss of all passengers and crew onboard.

But how could such a disaster happen? And has anyone ever been held accountable for this atrocity?

Background to Pan Am Flight 103

It was around 18:00 on the evening of December 21, 1998, in the small Scottish border town of Lockerbie, Scotland, home to around 3,000 people. With four days to go until Christmas, in the town’s Sherwood Crescent, families were busy wrapping presents while children waited with excited anticipation for the start of the festive period just around the corner.

Simultaneously, at London-Heathrow Airport (LHR), located some 330 miles (528km) south of Lockerbie across the border in England, a Pan Am Boeing 747-121 registered N739PA and named ‘Clipper Maid of the Seas’ was pushing back from its gate at the airport’s Terminal Three with 259 passengers and crew onboard. That night, the plane would be operating flight number PA103 from Heathrow to John F. Kennedy International Airport (JFK) in New York.

N739PA had entered service with Pan Am on February 12, 1970, and had completed 16,497 flights and logged 72,646 flight hours operating exclusively for the airline during its career.

In the aircraft’s vast cabin were passengers of all ages, either heading home for Christmas while others were traveling to New York to spend time with family and friends for the holiday season. The 259 passengers on Flight 103 originated from 21 different countries, with the vast majority holding United States (US) passports.

Among those waiting to board the flight were 35 US students who had spent six to 12 months in Europe on an exchange program from Syracuse University in New York State. There were also 12 children under the age of 10. The youngest passenger was nine weeks old, and the oldest was a 79-year-old woman from Budapest.

As families sat down for dinner in Lockerbie and settled into their seats on the 747 for the seven-hour flight to New York, no one at either location could have possibly known what horror would befall flight PA103 less than an hour later as the plane headed north on its transatlantic flight that night.

A routine departure from London

After take-off, the plane climbed to an altitude of 31,000 feet (9,500 meters). In the cockpit of N739PA, the flight crew was beginning their preparations for the oceanic portion of the flight.

At 18:58, the copilot on Flight 103 contacted Shanwick Oceanic Area Control in Ireland. This is the air traffic control station that assigns flight corridors to planes flying across the North Atlantic to the US to minimize congestion on the transatlantic air lanes. The co-pilot transmitted his aircraft’s flight number, altitude, and final destination to Shanwick, who acknowledged the transmission.

Four minutes later, at 19:02, the air traffic controller on duty in Shanwick received the flight plan for Flight 103 and checked it. He transmitted over the radio: “Clipper 103, take 59 north ten west to Kennedy.” But the controller received no response.

At 19:02, while the air traffic controller was passing instructions to Flight 103, the image of the flight’s transponder suddenly disappeared from his radar screen. When the radar returns reappeared a couple of seconds later, the controller in Shanwick saw multiple images on his screen of where Flight 103 should have been.

The inflight breakup of Flight 103

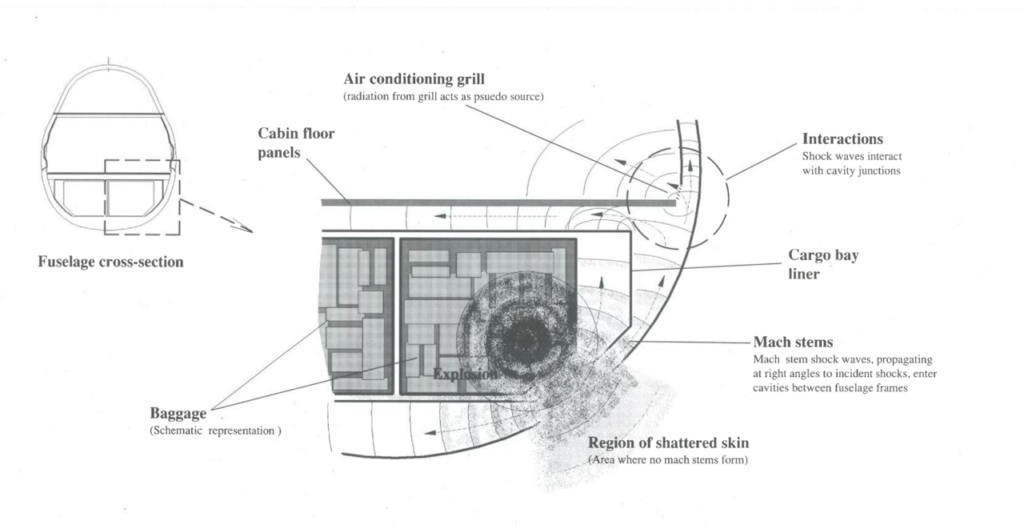

At around 19:02:50, 38 minutes after take-off from London, Pan Am Flight 103 had exploded as it passed overhead the Scottish town of Lockerbie. A timer-activated bomb located in the forward lower cargo compartment beneath the first class section of the cabin had suddenly detonated.

The subsequent explosion shattered the plane into several sections, all of which landed in an area covering roughly 850 square miles (2,200 square km) in and around Lockerbie.

Upon detonation, the aircraft immediately broke into three main sections, with the front end, including the cockpit, falling away first. The central section containing the fuel tanks, wings, and engines followed with the aft fuselage breaking away as the remaining wreckage fell towards the ground. This explains why the front section was found away from the main debris field on the outskirts of the town.

Falling wreckage from the stricken plane destroyed 21 houses in Lockerbie, killing an additional 11 people on the ground. Sherwood Crescent, where the aircraft’s wings and engines landed, was decimated, leaving a huge crater measuring 47 m (154 ft) long and with a volume of 560 m3 (20,000 cu ft; 730 cu yd) along with an intense inferno and the acrid stench of burning jet fuel.

The four Pratt & Whitney jet engines from the plane were reportedly still running at full power when they hit the ground at 500mph (800 kph).

According to an affidavit filed by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and made public by the US Department of Justice, witnesses in Lockerbie and the surrounding areas reported portions of the aircraft falling “from the sky, some of which appeared to be engulfed in flames.”

As pieces of the aircraft hit the ground, some exploded. One such incident created an explosion that witnesses described as a “mushroom cloud.”

All 243 passengers and 16 crew members onboard Flight 103 were killed. A further 11 people in houses along Sherwood Crescent also lost their lives.

The investigation begins

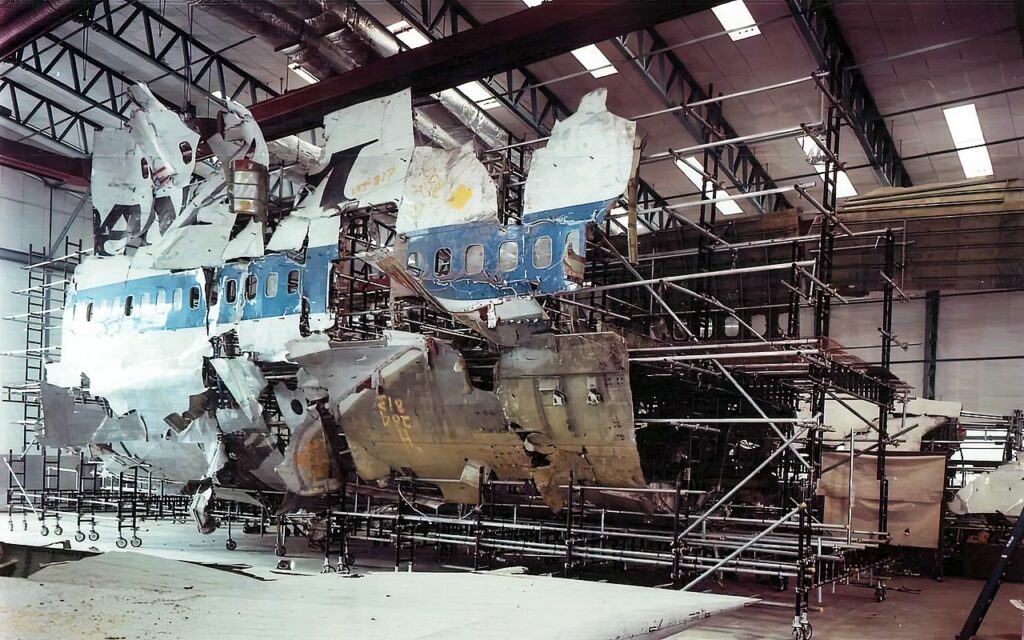

Over the following three years, investigators from the UK, the US, Germany, and several other countries collected thousands of pieces of evidence relating to Flight 103 and questioned more than 15,000 people across over 30 countries. The debris (said to be around four million separate pieces of aircraft, luggage, and human remains) was collected.

All parts of the airframe were taken away and stored to be painstakingly examined as part of the investigation process run by the UK’s Air Accident Investigation Branch (AAIB). The detached forward fuselage section, the only main section relatively intact, would eventually bear vital evidence as to what had happened to Flight 103.

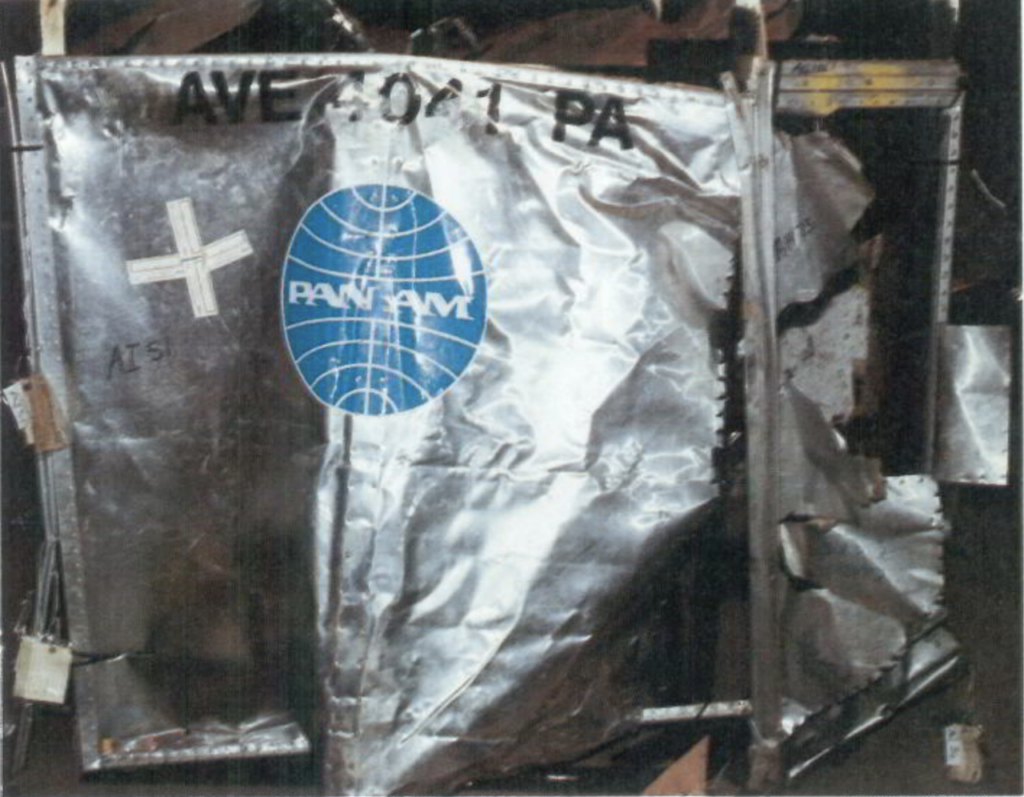

Examining the wreckage, the investigators made an important discovery. Pieces of wreckage from the left side of the front fuselage along with two luggage containers stowed in that section showed signs of an explosion. One of these containers had been loaded in Frankfurt and transferred onto Flight 103 at Heathrow.

Investigative breakthroughs

After weeks of testing, it was discovered that scraps of cloth and splinters from one suitcase showed traces of the chemicals RDX and PETN. Both are normally left in the wake of explosions triggered by the plastic explosive Semtex, which was produced in Czechoslovakia at the time.

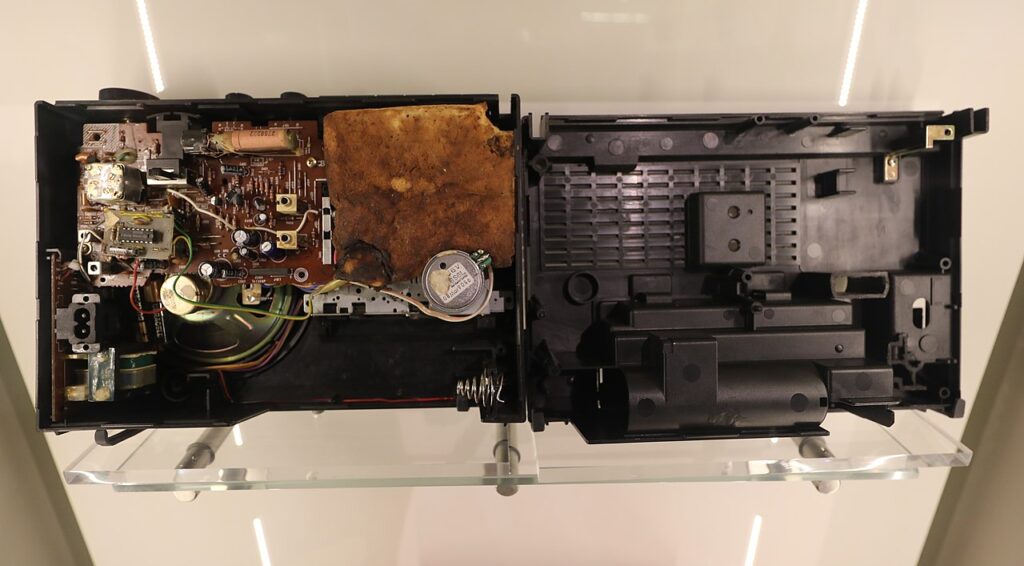

They also found a tiny fragment of an electrical circuit that was identified as part of a Toshiba radio cassette player. The scraps of cloth were found to be from a pair of trousers sold only by a specific clothing shop on the Mediterranean island of Malta.

The investigators concluded that an improvised explosive device had been concealed in the cassette player, wrapped in the trousers, which had then been placed in a brown Samsonite suitcase. This finding was revealed in the official report of the accident published by the AAIB in July 1990 – 19 months after the crash.

From these tiny but crucial pieces of evidence, the investigators were able to rule that a bomb, rather than mechanical failure, had caused the explosion and the downing of Flight 103.

It was discovered through tracking pieces of luggage that the brown Samsonite suitcase had been placed on an Air Malta flight to Frankfurt and subsequently transferred onto a Pan Am intra-European feeder flight carrying connecting passengers to Flight 103 for their onward journey between London and New York. Investigators also found that no passenger was listed as the owner of this bag and that it had traveled from Malta unaccompanied.

The finger of suspicion points toward Libya

Upon further intelligence being received and analyzed by both British and US authorities began to suspect Libyan agents as the prime suspects in planting the bomb onboard Flight 103. They looked back through old records and discovered that two Libyan men had been arrested in Senegal in

February 1988 with a device exactly like that which was suspected to have caused the loss of Flight 103.

In the summer of 1991, a man presented himself to US authorities who would become investigators star witness regarding the provenance of the bomb. Abdel Madshid Jiacha, a former Libyan secret agent, had subsequently been an assistant to the station manager of Libyan Arab Airlines at Malta airport. Upon questioning, he implicated two of his colleagues in the bombing of Flight 103 and gave further details.

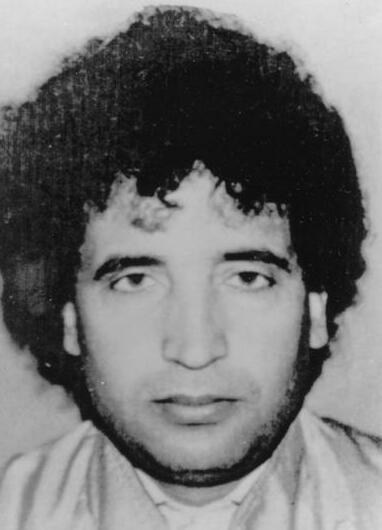

After months of questioning Jiacha, the FBI and the UK Metropolitan Police anti-terrorism branch announced that the attack on the Pan Am Boeing 747 had been carried out by two Libyan secret agents, namely Abdel Basset al-Megrahi, and Amin Chalifa Fhimah.

Jiacha had said he had observed these two men as they loaded the suitcase containing the bomb onto the plane in Malta that was bound for Frankfurt. He also said that the Libyan government had ordered the attack on Pan Am 103 as revenge for the US bombing of Tripoli and Benghazi in 1986.

The then-president of Libya, Colonel Muammar Gaddafi, initially refused to hand over the two suspects for questioning. However, due to increasingly stringent economic sanctions being imposed on the Libyan regime by the US and the United Nations Security Council, Gaddafi eventually capitulated and accepted the request to extradite the two men in 1998.

Terrorist trial and conviction

In 2001, at a special court in Scotland, over whose land the crime had been committed, and following an investigation that involved interviewing 15,000 people and examining 180,000 pieces of evidence, al-Megrahi was convicted of the bombing and was sentenced to 20 years in prison, later increased to 27 years.

The other man indicted, Lamin Khalifa Fhimah, was eventually acquitted. Upon al-Megrahi’s conviction, the Libyan government agreed to pay damages to the families of the victims of the attack.

In 2009, al-Megrahi, having served eight years of his 27-year sentence, was diagnosed with terminal cancer. Following a series of intense and highly contentious legal hearings, al-Megrahi was released from prison in Scotland on compassionate grounds in August 2009 and was allowed to return to Libya.

Facing a huge backlash from families of those US citizens who had died on Flight 103, the United States government strongly disagreed with the Scottish government’s decision to release al-Megrahi. It lobbied heavily that he remain in jail. However, with no legal jurisdiction over the case, and with the European Court of Human Rights also entering the fray, the Scottish government stuck by its decision to release al-Megrahi.

Al-Megrahi flew from Edinburgh Airport (EDI) to Tripoli on August 20, 2009, and was met at Tripoli Airport (TIP) by Colonel Gaddafi’s son, Saif Gaddafi. Upon arrival back in his homeland, al-Megrahi was treated like a national hero. He eventually died from cancer in May 2012.

Despite paying $2.7 billion in compensation to the families of those who died, Libya has never officially admitted responsibility for the bombing of Flight 103, and Colonel Gaddafi himself was overthrown and assassinated by Libyan rebel militia fighters in October 2011.

There were high-level calls from US authorities in 2020 for Libya to extradite a further five suspects to the US that the FBI wanted to question about their possible involvement in the attack on Pan Am Flight 103.

However, with compensation paid in full and with the Libyan authorities considering the matter closed, there have been no further suspects being extradited or questioned by any country over the terrorist attack on Flight 103.

Remembering the deceased

All passengers’ bodies bar seven were recovered from the area surrounding the crash site. Of the 11 that perished on Sherwood Crescent, there were no meaningful remains found in the aftermath of the crash that could be recovered for burial.

The main UK-based memorial for the victims is at Dryfesdale cemetery, located about one mile (1.5 kilometers) west of Lockerbie. There is a semicircular stone wall in the garden of remembrance with the names and nationalities of all the victims along with individual funeral stones and memorials.

There are also memorials in the church in Lockerbie where a plaque listing the names of all 270 victims appears. In Lockerbie Town Hall, a stained-glass window was installed depicting flags of the 21 countries whose citizens lost their lives in the disaster. There is also a book of remembrance at Lockerbie Public Library and another at Tundergarth Church, close to where the cockpit section of N379PA was found in a field on the outskirts of the town.

In Sherwood Crescent itself, which bore the brunt of the impact as N739PA crashed to earth, there is a garden of remembrance for the residents of Lockerbie who lost their lives.

All those who died as a result of the downing of Flight 103 are also remembered on a specifically dedicated memorial in Arlington Cemetery, just outside Washington DC in Virginia, United States. The group of students from Syracuse University heading home for Christmas also have their own dedicated memorial on their university campus.

Conclusion and legacy of Flight 103

The tragic events of 35 years ago shocked the world and the accident involving Pan Am Flight 103 remains the worst single aviation disaster in UK aviation history. However, many security procedures were changed after the event which means that air travel is now safer for all of us than it ever has been.

A little-known fact about the flight is that Flight 103 was delayed while sitting at the gate at Heathrow for around 30 minutes while de-icing continued and paperwork was completed on the flight deck.

Had this delay not occurred, then Flight 103 would have been well past Lockerbie and would have exploded as the flight headed out over the North Atlantic that night. Had this occurred, then little evidence might have been recovered from the seabed preventing the investigators from piecing together what exactly happened to N739PA “Clipper Maid of the Seas”.

While acts of terror against commercial flights have been an ever-present threat since commercial airline flights were introduced decades ago, commercial air travel remains one of the safest forms of travel. And without such flights being available to many of us, the world would be a much larger place in which to live.