Revised calculations indicate that the upper stage of a Chinese Long March 3C rocket, launched in 2014, is going to crash into the Moon on March 4, 2022.

The object was previously misidentified as an upper stage belonging to a Falcon 9 rocket, built by Elon Musk’s SpaceX.

The case of mistaken identity was revealed by Bill Gray, the same astronomer who first identified the object as a spent Space X rocket and calculated its trajectory.

Gray explained his discovery, as well as the reason behind the misidentification, in a lengthy blog post published on February 12, 2022.

According to the astronomer, the object was first discovered by Catalina Sky Survey (CSS), a part of NASA’s planetary defense initiative, and assumed to be an asteroid. The data was posted publicly, which led astronomers across the world to calculate its path and discover its man-made nature.

At the time it appeared that object’s trajectory followed that of a Falcon 9 second stage, which launched a Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR) satellite in February 2015.

“Essentially, I had pretty good circumstantial evidence for the identification, but nothing conclusive. That was not at all unusual. Identifications of high-flying space junk often require a bit of detective work, and sometimes, we never do figure out the ID for a bit of space junk,” Gray wrote.

Fast-forward to late January 2022, just a few weeks before the object was expected to collide with the Moon, and Gray’s announcement received international attention, causing uproar in the media.

Renewed interest prompted further investigation into the origin of the object. Subsequently, Gray received an email from Jon Giorgini who works at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Giorgini pointed out that the difference between the trajectory of the object in question and the second stage of the Falcon 9 that launched the DSCOVR is greater than initially thought.

“That prompted me to look for earlier space missions that might account for the object. It couldn’t have been up all that long before, because this is a large, bright object; somebody would have seen it. So it had to have been launched not long before March 2015, in a high orbit going past the moon. Few objects go that high; most stay relatively near the earth,” Gray explains.

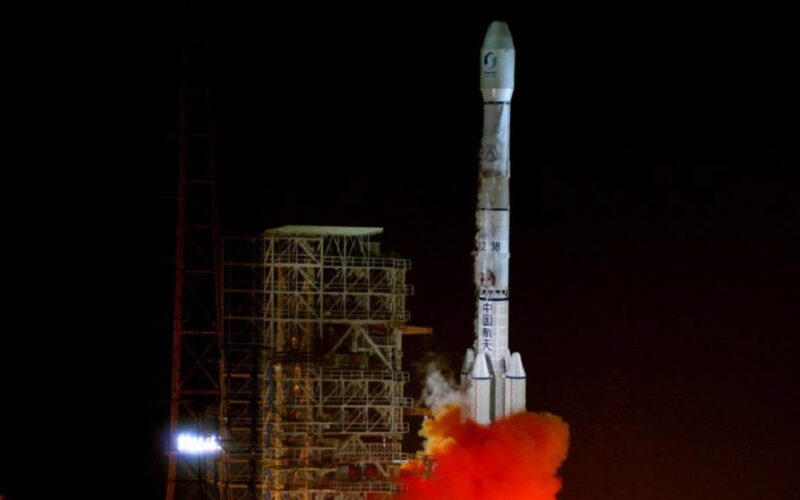

The nearest candidate was the Chinese Chang’e 5-T1 mission, launched in October 2014. It carried an experimental spacecraft towards the Moon in preparation for the Chang’e 5, and lifted-off onboard a Long March 3C/G2 rocket.

Gray ran the calculations once again, and the expected orbit of the Chinese rocket’s upper stage showed remarkable similarity with the orbit of the mystery object on course to collide with the Moon.

“If we assume that [Chang’e 5-T1’s – AeroTime] perigee was just above the atmosphere (as it usually is), then it happens about half an hour after launch time, and the ground path starts out near the launch site in China and proceeds almost due East. In short, it looks exactly like a Chinese lunar mission ought to look in every particular,” Gray writes.

The calculations were double-checked using additional information from small satellites launched into space on the same rocket through a ‘satellite rideshare’ program and proved to be correct.

“In a sense, this remains “circumstantial” evidence. But I would regard it as fairly convincing evidence, the sort where the jury would file out of the courtroom and come back in a few minutes with a conviction. So I am persuaded that the object about to hit the moon on 2022 Mar 4 at 12:25 UTC is actually the Chang’e 5-T1 rocket stage,” Gray adds.

According to Gray, the whole situation proves that both space agencies and companies do not do a good-enough job when tracking objects in deep space, as US Space Force radars barely reach objects beyond Low Earth Orbit, and SpaceX does not know where the second stage of its Falcon 9 ended up after the deployment of DSCOVR.

Hence, Gray’s original calculations were not double-checked in time, which led to an avalanche of false reporting.

According to the astronomer, the flight vectors of all discarded second stages should be publicly available, and a centralized initiative be implemented to keep track of high-orbiting junk, rather than leaving the job to space enthusiasts.

“I’d also advocate for attacking the problem on an international basis. This isn’t just a US (or Chinese) problem.” Gray concludes.