Late January 2020 saw several sources claiming that the Russian state-owned corporation Rostec announced the start of the development of PAK DP, or a “perspective aviation complex for long-range interception”. The plane, developed under that project, is most widely known as the MiG-41.

It was not the first time the start of its development was supposedly announced, and this new announcement was, to be frank, rather dubious. In all essence, the news was kicked up by a line in a Rostec press release dated January 22, and named “MiG-31BM: the high-flying bird”. The text was dedicated to the day of Air Defense Forces (a branch of the Russian military that no longer exists since the 90s) and celebrated the history of the MiG-31 high-speed interceptor, from its creation to the latest modernization. The last paragraph of the release stated that the next generation of this type of fighter jet, the PAK DP, was currently in development.

Any official announcements mentioning this program are extraordinarily rare. So much so, that all previous starts of the development were already forgotten, and the line got turned into a brand new confirmation that Russia finally started working on its 6th generation fighter jet. Russian news outlet Ria Novosti was amongst the first to extrapolate the one line into a full story, regurgitating rumors and snippets of information about the MiG-41 that were already in circulation.

The problem is, there are a lot of those snippets, and rumours are even more numerous. Furthermore, first ones have an awful tendency to contradict latter ones, and all of them rarely originate from any official sources.

Unfortunately, it is impossible to untangle this situation without diving into the long, long story of Soviet and post-Soviet heavy interceptors: the entire family of very fast aircraft, its many dead ends, and the way they are inseparable from what many call the MiG-41.

Hypersonic dreams

In the late 60s, the MiG-25 Foxbat appeared, and it was a truly groundbreaking plane: the fastest air-breathing aircraft at the time, designed to intercept enemy targets at great distances and great speeds, and scare Western observers with myths about its extraordinary capabilities. Contrary to those myths, actual capabilities were very limited. Nevertheless, the plane could routinely reach Mach 2, and even cross Mach 3, albeit with a risk of consuming its own engines in the process.

Early MiG-25 (Image: Wikipedia)

The plane was focused solely on high-altitude interception, and meanwhile, the US was working on aircraft capable of penetrating an airspace at the lowest altitude possible. Such a practice – nullifying all newest advances in air defense – was baked into the latest generation of American bombers, from the brand new General Dynamics F-111 Aardvark to the Rockwell B-1 Lancer, which had just entered development. On top of that, the MiG-25 was no longer the fastest bird in town: SR-71 Blackbird had just started flying, a reconnaissance plane the Foxbat could neither catch up with nor shoot down.

There was a need for a new heavy interceptor that could fly faster, carry more powerful armament, and most importantly – be adapted to a more diverse set of missions. Having a good low altitude performance would provide an additional ground attack capability, while the new phased array radar would plug the air defense gap in the Russian far north, beyond the coverage of an already stretched air defense network.

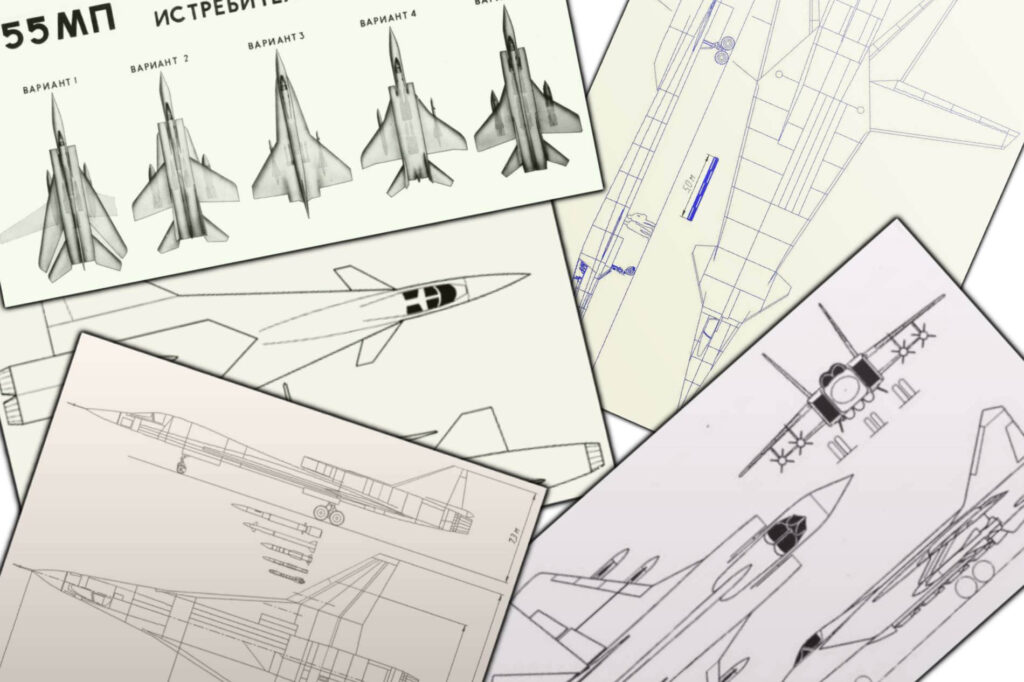

Right from the start, the MiG-25 was taken as a basis, with upgraded engines and avionics being supplemented with new wings that could offer more versatility. Different design bureaux offered different solutions to that, which resulted in the E-155MP project with half a dozen variants. Variable sweep and delta wings were looked into, but ultimately rejected: the most conservative variant with trapezoidal wings was chosen, and became the MiG-31 Foxhound, presented in the mid-to-late 70s.

MiG-31 (Image: Dmitriy Pichugin / Wikipedia)

Although it offered substantial improvements in terms of range, versatility and reliability, the speed remained the same. Modifications to the airframe were minimal. There was no need for that, as the idea of the ground attack variant was discarded, and there were no engines suitable for higher speed.

That was because Mach 3 – or more precisely, Mach 3.5 – was practically the limit of conventional turbojet engines. The flow of air at such speeds made the use of a compressor, a part that compressed air before ignition, difficult and unnecessary. A completely new kind of engine had to be devised if the plane was to reach higher speeds, and the Soviet Union – or anybody, for that matter – had no such engine.

Nevertheless, just as the development of the MiG-31 was being finalized in 1975, Mikoyan-Gurevich resumed the work on rejected solutions that could improve the performance of the interceptor even further. With an intel that Americans are developing their own planes capable of such speeds, the program was assigned a high priority, named “Project Maximum”, and led by Nikolay Matiuk – the chief engineer of MiG-25.

It consisted of two parts: Type 301 (interceptor) and Type 321 (bomber), two aircraft that would supplement a basic layout of the Foxbat with variable-sweep wings and deployable canards.

A new engine had to be developed. While particularities are unclear, and there is a lot of debate on the topic, the prospective power plant was said to be a two in one: a conventional turbojet and a ramjet housed under the same cowling, with a separator that would redirect a flow of air into one or another. A ramjet differs from a conventional jet engine in the fact that it lacks a compressor, and uses sonic shockwaves to compress air before ignition.

In theory, a combination of a turbojet and a ramjet is possible – SR-71 Blackbird used one, with special pipes redirecting the airflow around its turbojet to act as a ramjet. The solution for the Project Maximum, called D-102, was a lot more elegant. But it was never developed, and there is little proof it would actually work.

After switching such engines into ramjet mode, Type 301 interceptor would, in theory, maintain a cruise speed of 4,250 kilometers per hour (2,640 mph), and even reach a maximum speed of Mach 5, becoming the world’s first hypersonic fighter jet. Hypersonic – meaning, a speed over five times greater than the speed of sound – brings with itself yet another set of challenges, as the dynamics of flight change once again, just like they did when crossing from subsonic into supersonic speeds. Hypersonic vehicles have to be designed with that in mind. As far as we can tell, at least early variants of the Type 301/321 weren’t.

One of many possible variants of how Type 301/321 could have looked like (Image: dizzyfugu / Alternatehistory.com)

The aircraft retained the main outline of MiG-25 and MiG-31, except for overhauled wings and repositioned power plant. The dual-purpose engines were too massive to be fitted within the fuselage, as in earlier iterations of the interceptor. They had to be carried on top, in the rear section of the plane, giving it a distinct look present in most renders of MiG-41 to this day.

The new MiG takes shape

It is unknown what happened to the project Maximum, although quite clearly it fizzled out in the late 80s. According to some information from the 90s, the research on the airframe for the Type 301/321 was completed, and it was ready for the production of the prototype. There was no information on the engine though, and it is likely that it was far from ready. Perhaps, this problem was what really sank the Project Maximum.

But yet another ambitious project emerged in its place. It was led by a couple of engineers that came to Mikoyan-Gurevich from the Sukhoi bureau, and developed a new multifunctional long-range interceptor, designated Type 7.01 (sometimes written as MiG-701). The new plane had all the features of Type 301/321, but with a step towards simplification in the form of delta wings instead of variable-sweep ones.

Most importantly, although the position of the engines and the overall layout of the aircraft were retained, the idea of a combined turbojet/ramjet engine was dropped. The Type 7.01 was supposed to have a maximum speed of just 2,500 kilometers per hour (1,550 mph), which was deemed sufficient to completely replace the MiG-31 in its long-range role.

Rough blueprint of Type 7.01 (Image: Testpilot.ru)

The mind-bogglingly high speed was actually unnecessary thanks to the advancement of air-to-air missiles. Steps towards the next-generation armament were already undertaken with MiG-31: in the mid-80s its main missile, the R-33, was developed into the R-37 with twice the range (up to 300 kilometers), twice the speed (up to Mach 6) and a new radar. There also were several prototypes of MiG-31D, modified to carry a rocket that could reach a low-earth orbit, for either shooting down or deploying satellites.

With such weaponry and a new radar, the new aircraft on the basis of the Type 7.01 would constitute a proud successor to the MiG-25 and MiG-31 family, surpassing them in capabilities without a radical increase in speed, which would require equally radical advancement in technology.

But the project came too late: the 80s gave way to the 90s, the Soviet Union crumbled, and all the ambitious projects went with it. The 7.01 was officially closed in the mid-90s, but not before some consideration to turn it into a supersonic business jet.