On April 7, 1922, the first-ever mid-air collision of two airliners occurred between a de Havilland DH.18A and a Farman F.60 Goliath. None of the seven occupants survived.

The British airline Daimler Airway had started operating the de Havilland DH.18A, registered G-EAWO, two days before. The plane was flying mail from Croydon, south of London, bound for Le Bourget, Paris. On board were a pilot and a flight attendant.

Flying the opposing route was the Farman F.60 Goliath, registered F-GEAD, operated by the three-year-old French company CGEA (Compagnie Grands Express Aériens). The aircraft was transporting three passengers (an American couple and a French national).

The two aircraft were nearing Thieuloy-Saint-Antoine, 110 km (70 miles) north of Paris, in difficult weather conditions with drizzle and fog, at an altitude of 150 m (492 ft) when they collided. Six people died in the crash. The steward of the DH.18A was taken to a nearby hospital where he would later die of his injuries.

It is presumed that both flight crews were following the route by maintaining visual contact with the ground. At the time, airways followed geographic landmarks such as rivers and railways. As they were trying to find their way in the fog, pilots did not see each other in time to conduct evasive maneuvers.

This historical first would lead to several changes in international regulations, with the obligation to carry radio equipment in all airliners, and the establishment of well-defined and concerted air corridors. According to the Bureau of Aircraft Accidents Archives, priority rules were not the same in the United Kingdom and France at the time of the collision.

Additionally, the French state established a large network of “aeronautical lighthouses” a year later, in 1930, in order to increase safety in flight. The bright gas or electrical lamps that could be seen from 25 kilometers around helped the pilots find their way more reliably than natural landmarks. One of them would be installed on top of the Eiffel tower.

Commercial aviation would have to wait for the Second World War, with the Chicago Convention on International Civil Aviation in 1944, to see the development of air traffic control as we know it today.

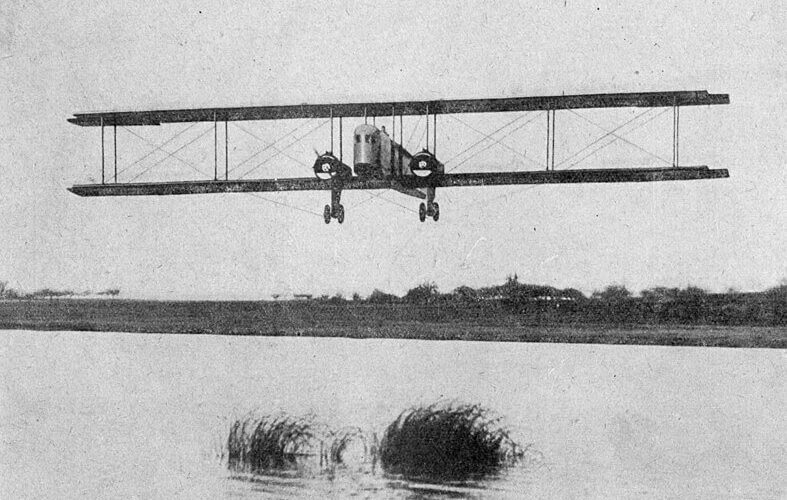

A de Havilland DH.18 (Credit: Public domain)