There are many ways to rank the largest aircraft manufacturers. We could look at the number of employees, the total revenue, or the number of aircraft produced. However, one of the best ways to assess a company’s size is by its market capitalization, or market cap.

The market cap of a company is the total value of its outstanding shares, effectively reflecting the market’s valuation of the company. It’s a good measure of the company’s equity and its size, although we’ll also look at the other metrics in our analysis.

All publicly traded aircraft manufacturers are considered, including those manufacturing commercial aircraft, private aircraft and defense products. Let’s dig in and discover the biggest aircraft manufacturers in the world in 2025.

The top 10 aircraft manufacturers by market cap

According to Companies Market Cap, there are 17 publicly traded aircraft manufacturers in the world today, representing a total market capitalization of $485.84 billion.

The biggest of all of these is Airbus, with a market cap of $146 billion, around $15 billion more than its competitor, Boeing. Although Boeing is second in terms of market cap, its earnings have taken a hit as a result of its ongoing issues. In 2024, Boeing posted a loss of $12.21 billion, compared to the most profitable manufacturer, Airbus, which posted profits of $6.75 billion.

Although no other manufacturer comes close to the market cap of Airbus and Boeing, there are some other interesting players in the top 10 list. Lockheed Martin remains a solid third-largest aircraft manufacturer, while companies like Embraer, Textron, and Bombardier vie for the lower positions.

You can explore the top 10 largest aircraft manufacturers in the chart below – hover or click on the columns for more details on each company.

Stay with us as we look at each of the 10 companies in more detail.

1. Airbus

Market cap: $146.29 billion

| Airbus key statistics | |

| Country | Netherlands |

| Founded | 1970 |

| Employees | 150,093 |

| Earnings in 2024 | $6.75 billion |

| Products | Commercial, business, helicopter, defense and space |

European aerospace corporation Airbus is the biggest aircraft manufacturer in the world in 2025, with a huge market capitalization of over $146 billion. Well known for its commercial aviation products, the company is also heavily involved in military aircraft, business jets, space vehicles and helicopters.

Despite having its fingers in many pies, commercial aviation is still the bread and butter of Airbus, accounting for around three-quarters of its revenue. In 2024, Airbus delivered 766 commercial aircraft and netted 826 new orders. Its best-selling model was the A320 family of aircraft, with over 600 jets delivered out of the 766 total.

According to Companies Market Cap, Airbus is the world’s 110th most valuable company by market cap. Its valuation is significantly higher this year than in 2024, growing almost 15% from $127.7 billion to its current status.

2. Boeing

Market cap: $130.39 billion

| Boeing key statistics | |

| Country | US |

| Founded | 1916 |

| Employees | 171,000 |

| Earnings in 2024 | -$12.21 billion |

| Products | Commercial, business, helicopter, defense and space |

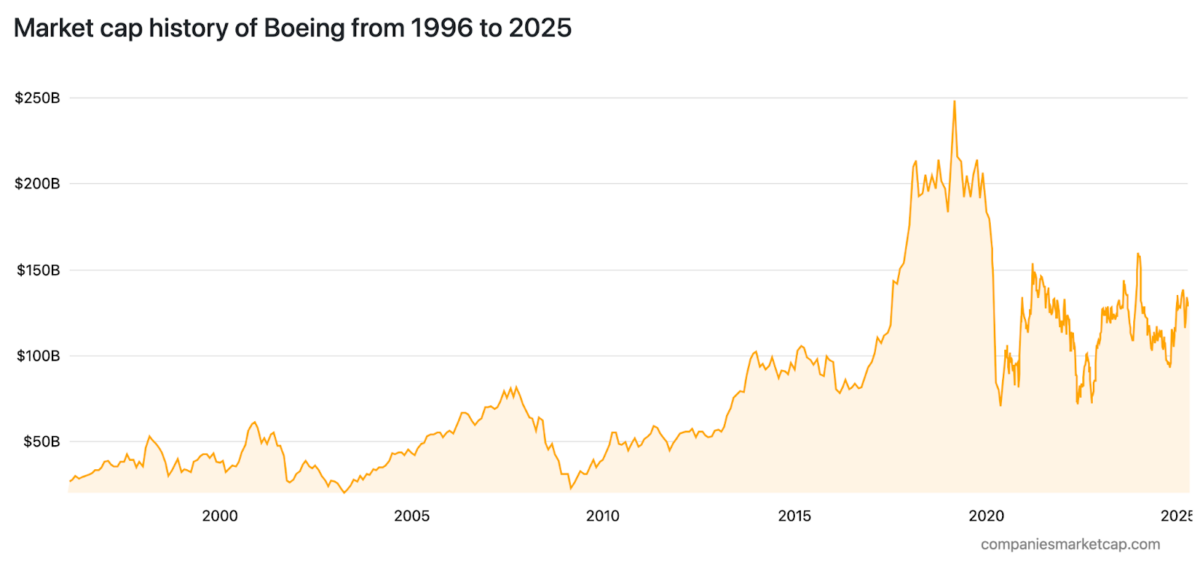

Boeing has had a tough few years, and its market cap reflects that. From a peak of $248 billion in 2019, the company took a massive pre-pandemic hit with the two fatal 737 MAX crashes. Then the pandemic bit, taking Boeing to a market cap low of just over $70 billion in May 2020.

It’s been up and down for the planemaker ever since, with a strong recovery in 2023 to finish the year at almost $158 billion. But 2024 didn’t start well, with the Alaska Airlines door plug blowout and subsequent FAA investigation forcing a 14% drop in market valuation by the end of the financial year.

2024 saw a drop in revenues too. The company posted a full year income of $66 million, 14% lower than in 2023 and reflective of Boeing’s lower-than-hoped-for aircraft deliveries. Boeing Commercial Airplanes delivered 348 aircraft in 2024, compared with 528 in 2023.

Like Airbus, Boeing has its fingers in many pies, but its Defense, Space and Security division is not doing much better than commercial aviation. For the 2024 full year, Boeing posted a loss of $5.4 billion due to rising costs of fixed price military contracts and issues with specific projects like the KC-46A and Starliner spacecraft.

In fact, the only profitable part of Boeing right now is its Global Services division, which provides aircraft maintenance, conversion, parts distribution and technology development. In 2024, Global Services posted earnings of $3.6 billion, up 4% from the year before.

3. Lockheed Martin

Market cap: $104.78 billion

| Lockheed Martin key statistics | |

| Country | US |

| Founded | 1995 |

| Employees | 122,000 |

| Earnings in 2024 | $6.22 billion |

| Products | Defense, helicopters and space |

Lockheed Martin operates in four business segments: Aeronautics, Missiles and Fire Control (MFC), Rotary and Mission Systems (RMS), and Space. Its business is firmly rooted in defense, producing iconic aircraft including the F-35 and F-16.

In 2024, the Aeronautics division delivered 110 F-35 fighter jets, up from 98 the previous year, and 16 F-16s, an increase from five in 2023. On June 28, 2024, the US Army awarded Lockheed a $4.5 billion contract to supply 870 Patriot Advanced Capability-3 (PAC-3) missiles and related hardware.

Although Lockheed still has a powerful market cap, it has dropped over 12% in the last year. This came as its share value plummeted following a worse-than-expected financial performance pinned to a $2 billion charge related to classified projects.

4. Hindustan Aeronautics

Market cap: $33.03 billion

| Hindustan Aeronautics key statistics | |

| Country | India |

| Founded | 1940 |

| Employees | 24,375 |

| Earnings in 2024 | $1.36 billion |

| Products | Commercial, defense and helicopters |

The largest aerospace company in India, Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL), has been making aircraft since 1940. Most well-known for its Tejas fighter jet, it also makes trainer aircraft, helicopters, drones and engines. It does make a passenger aircraft – the 19-passenger Saras turboprop, although only for military usage at present.

As well as making its own aircraft, HAL has worked under licensed production for several well-known vessels. These include the De Havilland Vampire, Folland Gnat, MiG-21 and Su-30. On the passenger side, it has built the HS 748 Avro and Dornier 228, sometimes called the HAL 228.

In October 2024, HAL was given Maharatna status, which allows the company to have more operational and financial autonomy. As part of the Make In India policy, HAL is planning to open logistics bases in Vietnam, Sri Lanka, Malaysia and Indonesia.

5. Dassault Aviation

Market cap: $27.1 billion

| Dassault Aviation key statistics | |

| Country | France |

| Founded | 1929 |

| Employees | 13,533 |

| Earnings in 2024 | $0.91 billion |

| Products | Business and defense |

Formed in 1929, 96 years ago, Dassault Aviation is a French manufacturer of defense products and business jets. It even once made a commercial airliner – the Mercure – designed to compete with the Boeing 737, although only 12 units were ever built.

On the business jet side, Dassault is well known for its Falcon series of aircraft. Its first Falcon was the 20/200, produced from 1963 until 1988. Its current production includes the trijet Falcon 900 and its upgraded sisters the Falcon 7X and 8X, as well as the twinjet Falcon 6X and forthcoming 10X.

For defense, its highly successful Mirage line has been iterated upon and developed since the 1960s, culminating in the Mirage 2000 which has been delivered to nine nations with over 600 units built. Complementing this is the Rafale, a competent multi-role fighter, along with various other products such as the Alpha Jet trainer, ejection seat systems and weapons.

Dassault had an excellent 2024, growing revenues by 5% and leveraging its software business to spur higher profits. As a result, its market cap of $27.1 billion is the highest in the history of the company, up over 50% since 2023.

6. Textron Aviation

Market cap: $13.25 billion

| Textron Aviation key statistics | |

| Country | US |

| Founded | 2014 |

| Employees | 35,000 |

| Earnings in 2024 | $1.04 billion |

| Products | General and business |

One of the youngest companies on our list, Textron Aviation was formed in 2014 after its parent company acquired Beech Holdings. This added the Beechcraft and Hawker product lines to its portfolio, joining Cessna as the three distinct brands the company produces.

With its roots firmly in general aviation, Textron is now the custodian of the wildly popular Cessna piston aircraft. Its current production includes the Skyhawk, Skylane and Stationair. In addition to these, it produces various turboprops, including the Caravan and SkyCourier, as well as the Citation range of business jets.

From Beechcraft, the company builds and maintains a range of products, including the King Air, Denali and Bonanza, while the Hawker brand is limited to service and maintenance only. Alongside all these, the company builds trainers and light attack aircraft for defense.

The company didn’t have an easy 2024, with a significant work stoppage impacting profits. A four-week strike by machinists led to delayed aircraft deliveries, reduced production and an estimated $30 million loss for the company. As a result, it finished 2024 with a market cap 23% lower than in 2023.

7. Embraer

Market cap: $8.74 billion

| Embraer key statistics | |

| Country | Brazil |

| Founded | 1969 |

| Employees | 19,179 |

| Earnings in 2024 | $0.55 billion |

| Products | Commercial, business, general and defense |

Based in São José dos Campos, just outside of São Paulo, Brazil, Embraer is known as the third-largest commercial aircraft manufacturer. Its ERJ and E-Jet families have become solid foundations of the regional aviation industry, and its newest and largest iteration, the E195-E2, is proving popular with airlines around the world.

But Embraer is about more than just commercial aircraft. Also in its wheelhouse are a variety of defense platforms, including the Super Tucano light attack jet and its capable C-390 Millennium transporter. It also excels in the business jet market with its Praetor and Phenom, and still produces the EMB 202 Ipanema crop duster aircraft.

Embraer has had an excellent few years recently, growing its market cap substantially from around $4 billion in 2018 to its current valuation of over $8 billion. In 2024, it reported revenues of $6.4 billion, up 21% year on year, largely driven by increased sales of its commercial and bizjet products.

8. Bombardier

Market cap: $5.5 billion

| Bombardier key statistics | |

| Country | Canada |

| Founded | 1942 |

| Employees | 17,100 |

| Earnings in 2024 | $0.73 billion |

| Products | Business |

Canadian manufacturer Bombardier is a shadow of its former self since selling off its commercial aviation business to focus on executive jets. From a high of over $20 billion market cap in 2000, its present valuation of $5.5 billion reflects a more streamlined operation.

From a portfolio that covered regional jets and turboprops, military trainers and aerial firefighting platforms, Bombardier now produces just four different aircraft. The Challenger 300 and 600 are smaller (but still sizable) business jets, while the Global series includes some of the largest executive jets in the industry.

In 2024, Bombardier delivered 146 aircraft and reached revenues of $8.7 billion. As of the end of December 2024, its backlog totals $14.4 billion.

9. Korea Aerospace Industries

Market cap: $5.28 billion

| Korea Aerospace Industries key statistics | |

| Country | South Korea |

| Founded | 1999 |

| Employees | 5,222 |

| Earnings in 2024 | $0.14 billion |

| Products | Defense, helicopters and space |

Korea Aerospace Industries, better known as KAI, is South Korea’s leading aerospace company. It has developed military aircraft such as the T-50 Golden Eagle trainer and the KF-21 Boramae fighter, as well as the KT-1 Woongbi, a turboprop trainer aircraft used both domestically and in countries such as Indonesia.

While defense is at the heart of KAI’s business, the company is steadily expanding into other areas, including satellites and space launch components. It also produces helicopters for military use, and has worked with Airbus to develop a civil helicopter known as the KAI LCH.

KAI has posted steady growth over recent years. In 2024, the company recorded revenue of around KRW 3.4 trillion (approx. $2.5 billion). It has set its sights on moving into the commercial aviation market through parts manufacture in partnership with Airbus and Boeing.

10. Joby Aviation

Market cap: $4.81 billion

| Joby Aviation key statistics | |

| Country | US |

| Founded | 2009 |

| Employees | 1,777 |

| Earnings in 2024 | -$0.6 billion |

| Products | eVTOL |

Joby Aviation is a pioneering electric aviation company based in California, best known for its work on electric vertical takeoff and landing (eVTOL) aircraft. Founded in 2009 by entrepreneur JoeBen Bevirt, Joby has become one of the most closely watched players in the emerging advanced air mobility (AAM) sector.

As of 2025, Joby remains pre-revenue in terms of aircraft sales, but it has made significant progress toward FAA certification of its flagship eVTOL aircraft. The all-electric vehicle seats four passengers plus a pilot, boasts a range of around 100 miles, and can cruise at speeds of up to 200 mph.

Joby aims to receive FAA certification by late 2025 or early 2026, and to launch commercial operations shortly thereafter. Challenges remain, especially around regulatory approvals, public acceptance of eVTOLs, and infrastructure buildout. Nevertheless, Joby remains one of the most credible contenders in the race to bring flying taxis to the real world.